图1 肌少性肥胖的发病机制

Fig. 1 Pathogenesis of sarcopenic obesity

徐 磊1,李春艳2,陈 宁2,*,范晶晶2,*

(1.武汉体育学院研究生院,湖北 武汉 430079;2.武汉体育学院健康科学学院,天久运动营养食品研发中心,湖北 武汉 430079)

摘 要:老年人肌少性肥胖(sarcopenic obesity,SO)是一种伴随着肥胖的骨骼肌质量和功能下降的老年性疾病,多发于老年人群而严重影响其生活质量。大量研究结果表明随着年龄的增长,即使体质量不变,老年人身体组成也会逐渐改变,肌肉质量功能下降,脂肪比例上升且主要堆积在肌肉组织、内脏器官,整体表现为肌肉脂肪量上升、炎症因子增多、生长激素水平下降、营养摄入不足、活动量降低、神经元功能下降以及胰岛素抵抗等,这些现象都与SO相关。从分子水平阐述其相关机制,研究者发现骨骼肌蛋白质合成与降解、骨骼肌糖脂代谢以及相关细胞因子均参与SO代谢通路的调控。运动干预、热量限制及蛋白质、VD、β-羟基-β-甲基丁酸盐、肌酸和乳清蛋白的摄入均可在一定程度上起到防治SO的效果。由于国内外对于SO的判断标准、发病机制以及防治手段仍不统一,给SO研究带来了较大难度。本文对国内外最新研究报道进行整理总结,从SO的定义、引起因素、涉及的细胞信号调控通路以及防治策略(运动或营养食品干预)等方面进行了综述,为SO治疗提供新思路。

关键词:肌少性肥胖;病理机制;信号调控通路;防治策略

老年人肌肉减少症最早于1989年提出,用来描述老年人肌肉减少和力量衰减[1]。肌肉组织增龄性丢失往往伴随脂肪组织的蓄积,因而也称之为“老年人肌少性肥胖(sarcopenic obesity,SO)”或“老年人肌肉衰减性肥胖”[2]。随着年龄的增长,老年人骨骼肌质量减少、肌肉力量衰退以及机体脂肪含量增加,并伴有生理性疾病、生活质量下降甚至死亡率上升等危险,部分地区SO患病率可高达41%[3]。

目前SO诊断标准包括:国际肌少症会议工作组诊断共识、亚洲肌少症工作组诊断共识、老年肌少症欧洲工作组诊断共识、美国国立卫生研究院基金会肌少症项目诊断共识[4],但由于人种、性别、环境以及测量技术等因素的影响,相关研究缺乏可比性,且缺乏统一的诊断标准。Baumgartner[5]使用双能X射线骨密度仪,利用相对骨骼肌质量指数(四肢骨骼肌质量除以身高的平方)诊断SO,当相对骨骼肌质量指数低于健康中青年人平均值2 个标准差,且体脂肪百分比超过同龄人群60%时诊断为SO。Davison等[6]利用人体测量学和生物电阻抗方法测量人体成分,间接测量人体的体脂肪和去脂含量,从而计算出人体肌肉量及脂肪量来定义SO:即体脂肪含量超过人群水平60%,且肌肉质量低于人群水平60%[6]。此外,Newman[7]与Marcus[8]等认为骨骼肌内脂肪组织量应是评判SO的单独指标,他们发现肥胖且骨骼肌质量高的老年人,其肌力以及日常活动能力并不理想。因此在今后对SO的判定中建议使用骨骼肌内脂肪组织量与上述提到的综合指标共同进行判定[9]。

研究发现SO与身体成分变化密切相关,机体脂肪量从中年到老年逐年增长并最终趋于平稳,同时肌肉质量在30 岁以后呈现逐渐减少的趋势,60 岁以后肌肉质量下降的速率更加明显[10]。肌肉质量的减少会导致机体基础代谢率下降、体力活动能力减退以及机体能量消耗减少,从而引起脂肪的堆积[11]。另一方面,随着脂肪的堆积,促炎症细胞因子水平上升,导致肌肉质量与力量的衰退,最终引起增龄性肌肉减少症[12],加重老年人肌肉下降与脂肪堆积的恶性循环。

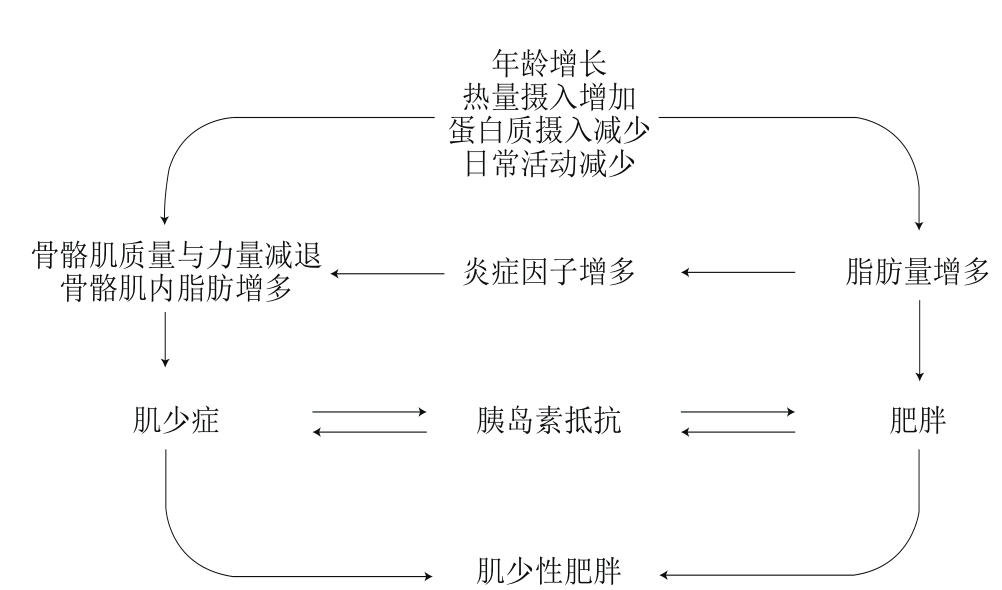

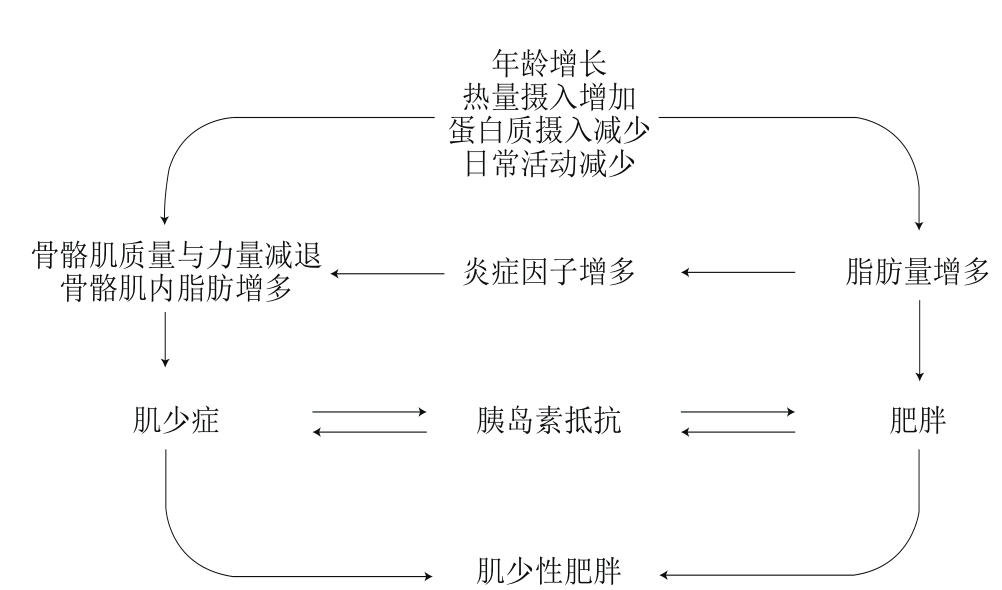

许多相互影响的因素会导致SO的发生与发展,包括体力活动的减少、蛋白质和微量元素摄入不足以及热量摄入过多等[13],可能引起骨骼肌质量、力量的下降,骨骼肌内脂肪以及脂肪组织含量增多,导致肌少症;也可能引起机体脂肪量增多,导致肥胖,最终导致SO;在这个过程中,炎症因子与胰岛素抵抗具有高度相关性(图1)。

图1 肌少性肥胖的发病机制

Fig. 1 Pathogenesis of sarcopenic obesity

蛋白质和VD摄入不足会导致骨骼肌质量、力量以及功能的衰退,引起不良的生理代谢反应[14]。VD作为人体必需的微量元素,可影响胰岛素分泌、合成及其敏感性,并抑制肥胖患者炎症机体代谢调节[15]。研究发现25羟基VD与四肢肌肉质量呈正相关,且SO与VD缺乏也息息相关[16-17]。

增龄性SO也与激素和肌肉营养信号的下降密切相关,慢性炎症状态、胰岛素抵抗以及激素失调等均可加速肌肉质量和力量丢失[13]。在脂肪组织中,由脂肪细胞或巨噬细胞浸润产生的白细胞介素(interleukin,IL)-6、肿瘤坏死因子(tumor necrosis factor,TNF)-α和脂肪因子等促炎症细胞因子、促炎症细胞因子上游调节炎症反应的瘦素或肌肉生成抑制素分泌水平改变,都可能会导致肌肉质量和功能的衰退[18-19]。促炎症细胞因子与脂肪量呈正相关,与肌肉质量呈负相关[20]。另外,肥胖且低肌肉量的老人超敏C反应蛋白和IL-6水平明显升高[12],因此,慢性炎症可能是造成肥胖者肌肉力量降低甚至加重肥胖的关键因素之一。

哺乳动物的肥胖与胰岛素抵抗炎症分子介导的细胞因子受体和胰岛素受体存在相关联的信号通道[21]。胰岛素加强蛋白质合成代谢,肥胖患者胰岛素抵抗可能促进肌肉分解;也有研究表明,胰岛素抵抗是导致肌肉力量下降及糖尿病老人表现出肌肉力量和质量丧失加速的一个独立相关因素[22]。肥胖也能抑制生长激素的产生,降低血浆类胰岛素生长因子Ⅰ[13]。最近的研究表明,不同肥胖表型神经-内分泌系统调控存在差异,与单纯肥胖病人和肌少症病人相比,SO病人生长激素的分泌显著下降[23]。睾酮是人体最重要的雄性激素之一,具有刺激组织摄取氨基酸、促进核酸与蛋白质合成以及肌纤维生长的作用,因而老年人肌肉质量与力量下降与机体睾酮水平降低也有关[24]。随着脂肪量增多与机体炎症的产生,骨骼肌细胞激素受体敏感性下降、激素利用率下降,从而影响骨骼肌蛋白质的合成,因此睾酮与生长激素水平低下都可能加重肥胖患者肌肉损伤。

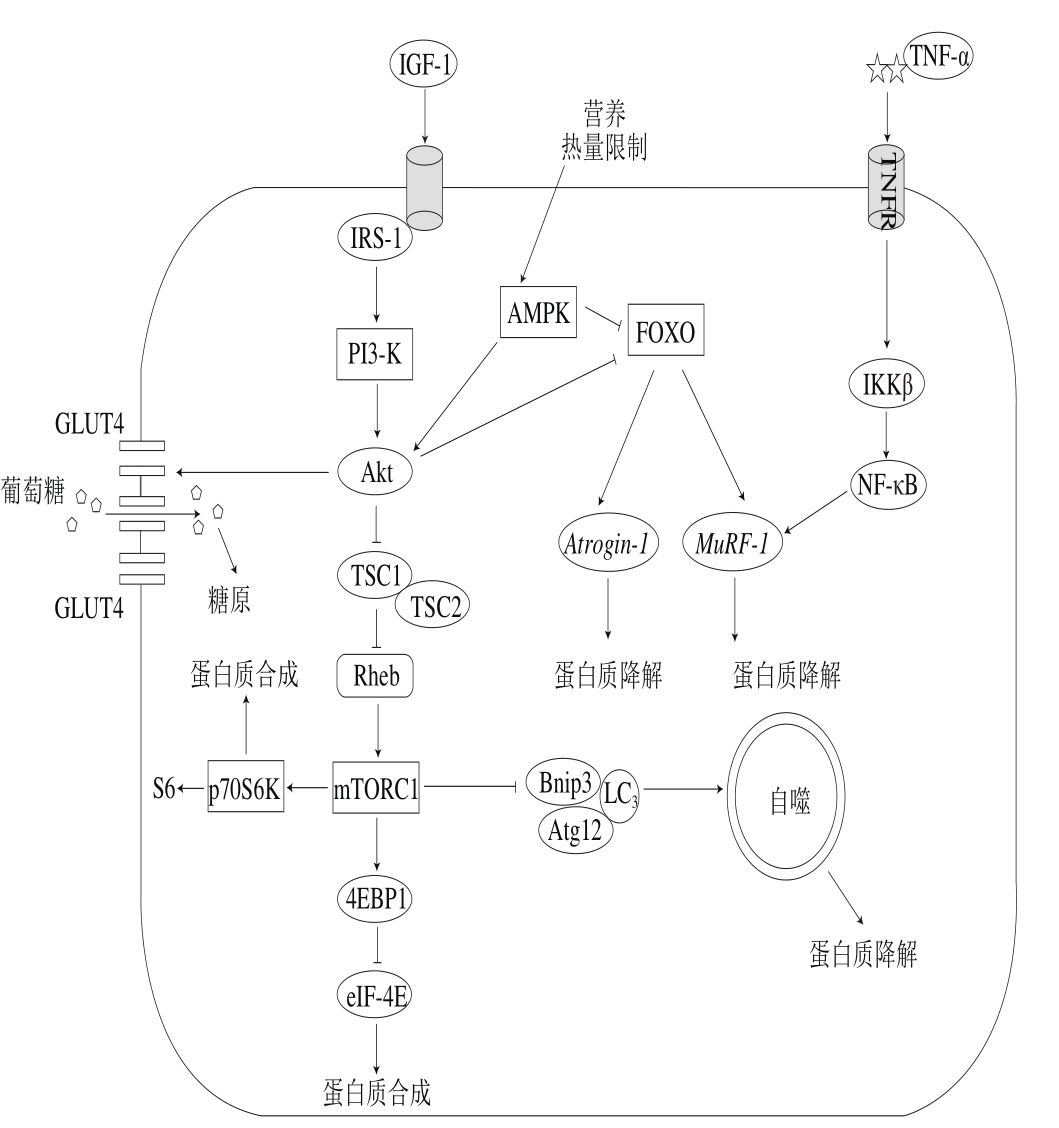

2.1 骨骼肌蛋白质的合成

磷脂酰肌醇3激酶(phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase,PI3-K)/蛋白激酶B(protein kinase B,Akt)/哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白(mammalian target of rapamycin,mTOR)信号通路为促进骨骼肌细胞内蛋白质合成的主要途径(图2)[25]。当PI3-K被其上游信号如生长因子、胰岛素等激活后,在细胞膜上将磷脂酰肌醇二磷酸(phosphatidylinositol(4,5) bisphosphate,PIP2)转化为磷脂酰肌醇三磷酸(phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)bisphosphate,PIP3),PIP3能与细胞内含有PH结构域(pleckstrin homolog domain)的信号蛋白Akt和3-磷酸肌醇依赖性蛋白激酶-1(3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1,PDK1)结合,促使PDK1磷酸化Akt蛋白的Ser308位点从而激活Akt[26-27]。活化的Akt磷酸化结节性硬化复合体蛋白(tuberous sclerosis complex,TSC)1和TSC 2,可下调其对小G蛋白同源物——脑内富含的小G蛋白Ras同系物(Ras homolog enriched in brain,Rheb)的负调控,进而使得Rheb富集,活化对雷帕霉素敏感的mTOR复合体1(mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1,mTORC1)。激活的mTORC1一方面可以通过使真核生物翻译起始因子4E(eukaryotic initiation factor 4E,eIF-4E)的抑制因子——4E结合蛋白1(4E binding protein 1,4EBP1)磷酸化后失活,解除4EBP1对eIF-4E的抑制作用而使蛋白质翻译效率提高,从而在单位时间内合成更多的蛋白质;另一方面可以使核糖体上的p70S6K激酶磷酸化被激活,直接增加蛋白质的合成[28]。

随着年龄的增加,骨骼肌的PI3-K/Akt/mTOR信号通路的信号传导受限,影响骨骼肌的内环境稳态。实验研究表明,老年小鼠骨骼肌在经过高频电流刺激之后,其肌肉中磷酸化的p70S6K和mTOR表达量下降[29]。此外,在对老年小鼠胫骨前肌进行6 h的高频电流刺激之后,发现4EBP1磷酸化显著增加[30],并且老年哺乳动物骨骼肌中的磷酸化的Akt水平是减少的[31-32]。尽管有研究发现老年肱二头肌中仅仅只有磷酸化的p70S6K(T421/S424)水平有显著性降低,磷酸化的p70S6K(T389)水平并没有显著性变化,但是在头颈部、舌头和四肢肌肉的p70S6K分子水平与年龄呈正相关[33]。上述研究表明,老年人骨骼肌中PI3-K/Akt/mTOR信号传导通路受损,骨骼肌蛋白质合成受限,引起蛋白质合成抵抗,最终导致衰老性肌萎缩。

图2 SO相关信号通路调控

Fig. 2 Signaling pathways involved in the regulation of SO

2.2 骨骼肌蛋白质的降解

2.2.1 泛素-蛋白酶体途径

泛素-蛋白酶体系统(ubiquitin-proteasome system,UPS)是细胞内蛋白质降解的主要途径,参与细胞内80%以上蛋白质的降解。UPS包括泛素(ubiquitin,Ub)、泛素活化酶E1、泛素结合酶E2、泛素蛋白连接酶E3、26S蛋白酶体和泛素解离酶DUBs。泛素蛋白连接酶E3是该途径的关键酶,决定着泛素-蛋白酶体途径的降解速率与特异性,在骨骼肌蛋白分解和肌肉萎缩过程中起着至关重要的作用,其中最为重要的两种E3为Atrogin-1和MuRF-1[34-35]。泛素-蛋白酶体降解蛋白质途径主要包含胰岛素类似生长因子1(insulin-like growth factor-1,IGF-1)/PI3-K/Akt/叉头状转录因子O亚家族蛋白(forkhead box O,FOXO)和细胞核转录因子κB抑制蛋白激酶β(inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B kinase β,IKKβ)/细胞核转录因子κB(nuclear factor kappa B,NF-κB)两个信号通路(图2)[28]。在IGF-1/PI3-K/Akt通路中,激活态的Akt从细胞膜转移到细胞核并磷酸化FOXO,磷酸化的FOXO被转运出细胞核后对靶基因Atrogin-1和MuRF-1失去调控,从而抑制蛋白质降解与肌萎缩;另外一个关键的通路就是IKKβ/NF-κB独立调控着MuRF-1的表达[36]。当肌细胞受到各种胞内外刺激后,NF-κB抑制蛋白(inhibitor of NF-κB,IκB)激酶被激活,从而导致IκB蛋白磷酸化与泛素化,进而被降解,NF-κB二聚体得到释放并转移至核内,调节MuRF-1以完成蛋白质的降解。因此,IGF-1/PI3-K/Akt/FOXO信号通路可以同时调节Atrogin-1和MuRF-1的表达,促进肌肉蛋白质的降解,而IKKβ/NF-κB通过调节MuRF-1的表达实现调控蛋白质的降解。通过转基因小鼠MISR(抑制NF-κB)和MIKK(激活NF-κB)研究发现,MIKK小鼠骨骼肌严重萎缩,而MISR小鼠骨骼肌并没有明显改变,其中MIKK小鼠MuRF-1表达增加,证明内源性激活NF-κB通路能够导致明显的肌萎缩[36]。2.2.2 溶酶体-自噬途径

自噬是指细胞吞噬自身蛋白或细胞器并使其包被进入囊泡,与溶酶体融合形成自噬溶酶体,降解其所包裹的内容物的过程,借此实现细胞本身的代谢和某些细胞器的更新。自噬溶酶体的形成主要包括3 个部分,第1个是依赖PI3-K/Akt/mTOR信号通路,通过mTOR抑制Atg1-Atg13-Atg17(哺乳动物同源物ULK1/2-mAtg13-FIP200)自噬相关复合物的形成[37];第2个信号通路由Atg6(哺乳动物同源物Beclin1)调控,Bcl-2的磷酸化使Bcl-2与Beclin1分离,Beclin1与Vps34以及Atg14形成Atg6(Beclin1)-Vps34-Atg14复合物,参与吞噬泡的形成[38];第3个信号通路介导自噬体的形成,Atg7和Atg10调节Atg12和Atg5结合,与Atg16形成Atg12-Atg5-Atg16复合体,参与自噬体的形成。之后LC3在Atg4的催化下,形成LC3-I,经Atg7和Atg3催化与自噬泡膜表面磷脂酰乙醇胺结合形成LC3-II,调节自噬体的延伸。当自噬体与溶酶体结合变成自噬溶酶体后,溶酶体中的蛋白酶可降解内容物,完成自噬过程[39]。通过衰老的哺乳动物骨骼肌中自噬变化的研究发现,衰老的小鼠足底肌肉Beclin1和LC3的表达量显著增加[40];另外,22 月龄小鼠的LC3-II/LC3-I比率显著性高于3 月龄的小鼠[41]。因此,衰老可能导致代偿性细胞自噬激活或自噬流障碍,肌蛋白质过多降解,从而导致衰老性肌萎缩。

2.3 骨骼肌糖代谢

骨骼肌是葡萄糖代谢的重要外周组织,占成年人体质量40%~50%,其葡萄糖代谢水平在调节全身血糖稳态和能量代谢中发挥着重要作用[42-43]。葡萄糖转运体4(glucose transporter 4,GLUT4)是骨骼肌内最重要的葡萄糖转运蛋白,其介导的葡萄糖跨膜转运至胞内是骨骼肌葡萄糖代谢的主要机制,GLUT4的转位和表达变化可以在一定程度上反映骨骼肌细胞的糖代谢状况。GLUT4的转位主要由PI3-K/Akt信号通路调控(图2)[44-45]。

SO多伴有胰岛素抵抗,细胞对葡萄糖的摄取能力受到抑制,引起血糖与血脂异常,加重SO症状[46],所以GLUT4转运体对缓解胰岛素抵抗、改善老年人SO起着至关重要的作用。胰岛素激活骨骼肌内胰岛素受体底物(insulin receptor substrate,IRS)和PI3-K,产生PIP3分别与Akt和非典型蛋白激酶C结合,促使GLUT4转位至表面细胞膜以摄取葡萄糖[45]。

在运动改善代谢障碍的老年人群骨骼肌胰岛素抵抗研究中,PI3-K/Akt信号通路受到众多研究者的关注。研究表明游泳运动可增强Wistar大鼠IRS-2、PI3-K和Akt的活性,同时增加GLUT4的蛋白表达[47]。然而,Krook等[48]认为骨骼肌内GLUT4转位和表达的影响与PI3-K/Akt信号通路无关,可能与AMP依赖的蛋白激酶(AMP-activated protein kinase,AMPK)信号通路有关。对肥胖Zucker大鼠进行为期7 周的跑台训练,强度从15 m/min持续10 min逐渐增加至22 m/min持续90 min,发现此运动方式可以上调GLUT4的蛋白表达,但IRS-1的酪氨酸磷酸化水平,并无明显变化[49]。这些研究似乎暗示PI3-K/Akt信号通路在运动调节骨骼肌内GLUT4的转位和表达中不起决定性作用,研究结果的不一致可能与采用的动物模型、运动的干预手段及检测的信号分子等不同有关。

3.1 运动干预

合理的运动(方式、持续时间以及强度)对SO有显著的预防和改善作用,对患有SO的老年人进行运动干预可以显著提高身体机能[50]。受试者在12 周内每周进行2~3 d的抗阻训练可引起肌肉肥大,同时Ⅰ型和Ⅱ型肌纤维的横截面积均有所增加,说明抗阻运动对老年人肌肉耐力和力量有促进作用[51]。对70~89 岁的受试者进行生活方式干预和独立实验,结果发现,联合运动(有氧、抗阻、平衡以及灵活)以及健康教育干预显著提高他们身体表现指数[52]。Davidson等[53]对腹型肥胖的老年男性和女性进行了为期6 个月的单一型和联合型运动训练(抗阻、有氧、抗阻结合有氧),结果发现联合型运动组减脂效果最好,抗阻运动组和联合型运动组骨骼肌质量与力量显著改善。因此联合型运动方式对SO有显著的改善效果,不仅可以减少脂肪含量,同时也能够抑制骨骼肌的萎缩或促进骨骼肌的生长。

抗阻运动作为防治SO的关键性干预方式,是一种安全且能有效维持并增加骨骼肌质量与力量、改善骨骼肌功能和提高老年人生活质量的干预方法[54]。肌卫星细胞是具有增殖、自我更新能力和参与骨骼肌修复的成肌前体细胞。大量研究表明,经过12 周抗阻运动后老年人肌卫星细胞含量增加近31%,停训3、10、60 d后肌卫星细胞含量保持在基础值之上,可见抗阻训练有利于激活肌卫星细胞增殖与分化[55]。Zanchi等[56]让Wistar大鼠进行为期3 个月的负重爬梯训练,发现抗阻运动组大鼠跖肌和比目鱼肌较对照组增加近12%,且MuRF-1、Atrogin-1的表达量分别下降41.64%和61.19%。研究人员让小鼠每3 d进行一次爬梯训练,为期5 周,发现其趾长伸肌中p70S6K与4EBP-1蛋白的磷酸化水平较对照组显著上升[57]。由此可见抗阻运动一方面有助于激活肌卫星细胞增殖与分化,产生新肌细胞,促进肌纤维的加粗;另一方面可以有效抑制由MuRF-1和Atrogin-1调控骨骼肌蛋白质的降解,且能上调p70S6K和4EBP-1蛋白的磷酸化水平,提高机体骨骼肌蛋白质的合成,从而稳定骨骼肌蛋白质合成与降解的动态平衡。

3.2 营养食品干预

3.2.1 热量限制与蛋白质摄入

通过热量限制可以缓解炎症所导致的骨骼肌萎缩,但是肥胖老年人单纯进行热量限制不能解决SO这一问题,应该增肌与减脂双管齐下,且不能只以体质量变化来衡量减脂效果,应结合身体成分或功能变化来衡量减脂效果[58]。

针对老年人体质量管理的简单干预是有争议的,因为通过饮食限制减肥的过程有可能引起肌肉减少症、骨质疏松以及营养物质缺失而产生危害,甚至导致死亡率的上升[59-61]。据报道,大约25%通过短期能量限制的减肥方法达到体质量减少的老年人,都会伴有瘦肌肉质量的减少[62-64]。此外,研究表明,体质量减轻后的反弹主要增加的是脂肪成分,因此体质量反弹可能加重SO[65-66],此外,营养干预后长期控制机体脂肪的比例与维持骨骼肌质量是至关重要的。

用于年轻人体质量管理的方法不能简单应用于低肌肉质量与虚弱的老年人群,应该更加重视老年人体质量控制的干预方式[67-68]。针对这类老年人,极低热量摄入的饮食方式(小于1 000 kcal/d)的营养干预法是不推荐的[62,66]。应保证200~750 kcal/d的适度能量同时配合蛋白质以及微量元素的摄入,每周体质量降低0.5~1.0 kg或6 个月减轻原体质量的8%~10%,同时保证每天每千克体质量摄入1 g的蛋白质以及适当的微量元素,这类饮食干预法对老年人群体质量管理更有效果[62,66,69]。考虑到体质量的反复增减所带来的危害,建议肌少性肥胖老年人长期改变饮食,并进行适当的体力活动干预。

3.2.2 VD的摄入

VD是重要的微量元素,其摄入量的减少会导致肌肉质量与力量的衰退、步态障碍、平衡能力下降以及摔倒风险的剧增,这些症状与SO相关[58]。VD与VD受体结合形成的复合体既能调控血钙浓度,影响胰岛素分泌与合成,也能刺激外周胰岛素靶细胞表达胰岛素受体,优化胰岛素敏感性,并抑制IL-1、IL-6、IL-8以及TNF-α等促炎症细胞因子的生成[15]。据报道,缺乏VD是中老年人群的常见问题[58],25羟基VD是人体内源性的VD,在光照的作用下直接转化为VD,正常人体内25羟基VD水平为75 nmol/L[70]。在美国的调查研究中,超过30%的70 岁以上的老年人体内25羟基VD含量低于50 nmol/L[71],肥胖也与低VD水平有关。此外,对社区老年人的横向研究发现,VD水平与身体活动能力存在直接联系,特别是25羟基VD水平低于75 nmol/L的老年人[72-74]。由此可见,VD对于维持老年人骨骼肌质量以及力量至关重要。

3.2.3 β-羟基-β-甲基丁酸

β-羟基-β-甲基丁酸(β-hydroxy-β-methyl-butyrate,HMB)是亮氨酸代谢过程中产生的天然化合物,具有促进骨骼肌蛋白质合成、抑制骨骼肌蛋白质降解以及降低机体炎症等作用,被广大健身爱好者以及运动员接受。研究表明,对养老院老年人实施2~3 g/d的HMB补充,一年后HMB组骨骼肌质量增加了0.88 kg[75]。同样的研究发现给社区老年人补充3 g/d的HMB且联合每周5 d的抗阻运动,HMB联合抗阻运动组瘦体质量增加0.8 kg,且上肢与下肢力量分别增加近15%与20%[76]。从这些研究可以看出,适量HMB的摄入加上联合运动(有氧、抗阻、平衡以及灵活训练)能改善老年人骨骼肌质量和力量,维持骨骼肌功能。

3.2.4 肌酸

肌酸是一种由甘氨酸、精氨酸及甲硫氨酸合成的含氮有机酸,适量补充肌酸能维持并改善老年人骨骼肌质量、力量和功能。Gotshalk等[77]将30 名58~79 岁的女性分为肌酸组和安慰剂组,分别注射0.3 g/(kg·d)肌酸与安慰剂,为期7 d,最后发现肌酸组受试者卧推、腿举、体质量、无脂肪体质量较安慰剂组显著增加,且串联步态以及站立完成时间显著缩短。此外,Devries等[78]将357 个老年人分为肌酸联合抗阻运动组和抗阻运动组进行为期6 周的干预,发现肌酸联合抗阻运动组受试者骨骼肌质量、力量以及功能表现都好于抗阻运动组。由此可见单纯的补充肌酸可以改善老年人的肌少症,但是在补充肌酸的基础上再联合抗阻运动效果会更好。

肌酸影响骨骼肌合成代谢的机制尚未研究透彻。大量实验表明摄入肌酸可使骨骼肌磷酸化4EBP1和p70S6K的水平、AMPK和GLUT4的蛋白水平上调[79]。但是,肌酸是通过激活PI3-K/Akt通路,使4EBP1和p70S6K磷酸化水平以及GLUT4蛋白水平的上调,促进蛋白质合成,增强葡萄糖的转运效率,从而起到维持骨骼肌质量、力量和功能的作用,还是通过其他途径来防治增龄性肌少症,此类机制性研究还较少。此外肌酸可以通过肌酸转运蛋白渗入骨骼肌,在ATP的作用下磷酸化成磷酸激酶,参与ADP-ATP供能系统,给骨骼肌供能。可是对老年人群中骨骼肌的肌酸转运蛋白数量以及功能变化的相关研究甚少。今后,在肌酸影响骨骼肌合成代谢机制这方面的研究还有待进一步深入,但是肌酸对维持老年人骨骼肌质量、力量以及功能起一定的作用。

3.2.5 乳清蛋白

乳清蛋白是一种氨基酸种类齐全,且比例均衡,并能提供人体必需蛋白质的优质蛋白质来源。其主要由α-乳球蛋白、β-乳白蛋白、牛血清蛋白、免疫球蛋白等组成,具有易消化吸收和增强机体蛋白质合成等功效,广泛运用于专业运动员和健美人群,也逐渐成为老年人的营养补剂。Bauer等[80]将380 名衰老性肌萎缩老年人分为VD乳清蛋白复合补剂组和对照组,进行为期13 周每天两次的干预,发现复合补剂组四肢骨骼肌显著增加,座位站立、步速以及平衡都有显著性的提高。研究人员对49 名73 岁左右老年人进行了两个阶段的实验,第一阶段,随机分为复合营养补充组(乳清蛋白为主)和对照组,6 周后发现复合物营养补充组较对照组瘦体质量和肌肉力量显著增强;第二阶段,在此前基础上联合运动干预,12 周干预后发现两组受试者瘦体质量和肌肉力量都增加,且复合营养补充组较对照组增加更为明显[81]。由此可见,单纯补充乳清蛋白对老年人群骨骼肌质量、力量以及功能都有一定的功效,但是配合适量肌酸、VD等一系列促进骨骼肌蛋白质合成的营养物对衰老性肌萎缩的防治效果更佳,再配合适量的运动训练(抗阻、有氧等)效果更为显著。

目前国际上对SO正在进行大规模研究,我国作为人口老龄化大国,这方面还处于空白阶段,未来加强对SO的关注是必然趋势。SO的定义缺乏精确化与统一化,且SO并不是肌少症与肥胖的简单结合,其病理较单纯肌少症与单纯肥胖更复杂,因此迫切需要一个统一的诊断标准。

骨骼肌作为机体主要能量代谢场所,调控着蛋白质合成、降解以及糖代谢,对维持机体能量稳态至关重要。临床上正研究开发调控骨骼肌蛋白合成、降解以及糖代谢相关基因蛋白药物,加强骨骼肌内坏境稳态,维持骨骼肌质量和功能,对SO起到防治作用。事实上SO作为一种老年慢性病,单一药物治疗效果并不理想,应引导老年人自主性生活方式的改变,通过运动或营养干预从而有效地预防和治疗SO,包括抗阻运动联合有氧运动、热量限制、蛋白质补充、VD、HMB、肌酸、乳清蛋白的摄入以及充足的光照。随着我国SO患病率逐年增高,未来开展SO研究以维持老年人肌肉质量与力量、提高生活质量和机体功能显得尤为重要。

参考文献:

[1] ROSENBERG I H. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance[J].Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 2011, 27(3): 337-339.

[2] CRUZ-JENTOFT A J, BAEYENS J P, BAUER J M, et al. Sarcopenia:European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European working group on sarcopenia in older people[J]. Age and Ageing, 2010, 39(4): 412-423. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afq034.

[3] CAULEY J A. An overview of sarcopenic obesity[J]. Journal of Clinical Densitometry, 2015, 18(4): 499-505. DOI:10.1016/j.jocd.2015.04.013.

[4] 金菊香, 孙丽娟, 张丽玲, 等. 肌少症的流行病学和诊断评估研究进展[J]. 中华老年医学杂志, 2015, 34(10): 1154-1157. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-9026.2015.10.029.

[5] BAUMGARTNER R N. Body composition in healthy aging[J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2000, 904(1): 437-448.

[6] DAVISON K K, FORD E S, COGSWELL M E, et al. Percentage of body fat and body mass index are associated with mobility limitations in people aged 70 and older from NHANES III[J]. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2002, 50(11): 1802-1809.

[7] NEWMAN A B, KUPELIAN V, VISSER M, et al. Sarcopenia:alternative definitions and associations with lower extremity function[J]. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2003, 51(11):1602-1609.

[8] MARCUS R L, ADDISON O, DIBBLE L E, et al. Intramuscular adipose tissue, sarcopenia, and mobility function in older individuals[J]. Journal of Aging Research, 2012, 2012(10): 629-637.DOI:10.1155/2012/629637.

[9] ZAMBONI M, MAZZALI G, FANTIN F, et al. Sarcopenic obesity:a new category of obesity in the elderly[J]. Nutrition, Metabolism,and Cardiovascular Diseases, 2008, 18(5): 388-395. DOI:10.1016/j.numecd.2007.10.002.

[10] STRUGNELL C, DUNSTAN D W, MAGLIANO D J, et al. Influence of age and gender on fat mass, fat-free mass and skeletal muscle mass among Australian adults: the Australian diabetes, obesity and lifestyle study (AusDiab)[J]. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 2014,18(5): 540-546. DOI:10.1007/s12603-014-0464-x.

[11] ROUBENOFF R. Sarcopenic obesity: does muscle loss cause fat gain?lessons from rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis[J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2000, 904(1): 553-557.

[12] SCHRAGER M A, METTER E J, SIMONSICK E, et al. Sarcopenic obesity and inflammation in the InCHIANTI study[J]. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2007, 102(3): 919-925. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00627.2006.

[13] WANG C Y, BAI L. Sarcopenia in the elderly: basic and clinical issues[J]. Geriatrics and Gerontology International, 2012, 12(3): 388-396. DOI:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00851.x.

[14] CAMPBELL W W, LEIDY H J. Dietary protein and resistance training effects on muscle and body composition in older persons[J]. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 2007, 26(6): 696S-703S.

[15] 王雪芹, 黄乙欢, 赵柯湘, 等. 肌少性肥胖与代谢综合征[J].国际老年医学杂志, 2016, 37(3): 138-141. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-7593.2016.03.013.

[16] LIU G, LU L, SUN Q, et al. Poor vitamin D status is prospectively associated with greater muscle mass loss in middle-aged and elderly Chinese individuals[J]. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2014, 114(10): 1544-1551; 1542. DOI:10.1016/j.jand.2014.05.012.

[17] KIM T N, PARK M S, LIM K I, et al. Relationships between sarcopenic obesity and insulin resistance, inflammation, and vitamin D status: the Korean sarcopenic obesity study[J]. Clinical Endocrinology,2013, 78(4): 525-532. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04433.x.

[18] FANTUZZI G, MAZZONE T. Adipose tissue and atherosclerosis:exploring the connection[J]. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis,and Vascular Biology, 2007, 27(5): 996-1003. DOI:10.1161/ATVBAHA.106.131755.

[19] SAKUMA K, YAMAGUCHI A. Sarcopenic obesity and endocrinal adaptation with age[J]. International Journal of Endocrinology, 2013,2013(2): 1-12. DOI:10.1155/2013/204164.

[20] CESARI M, KRITCHEVSKY S B, BAUMGARTNER R N, et al.Sarcopenia, obesity, and inflammation: results from the trial of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition and novel cardiovascular risk factors study[J]. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2005,82(2): 428-434.

[21] BASTARD J P, MAACHI M, LAGATHU C, et al. Recent advances in the relationship between obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance[J]. European Cytokine Network, 2006, 17(1): 4-12.

[22] PARK S W, GOODPASTER B H, STROTMEYER E S, et al.Accelerated loss of skeletal muscle strength in older adults with type 2 diabetes: the health, aging, and body composition study[J]. Diabetes Care, 2007, 30(6): 1507-1512. DOI:10.2337/dc06-2537.

[23] WATERS D L, QUALLS C R, DORIN R I, et al. Altered growth hormone, cortisol, and leptin secretion in healthy elderly persons with sarcopenia and mixed body composition phenotypes[J]. Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences,2008, 63(5): 536-541.

[24] ALLAN C A, STRAUSS B J, MCLACHLAN R I. Body composition,metabolic syndrome and testosterone in ageing men[J]. International Journal of Impotence Research, 2007, 19(5): 448-457. DOI:10.1038/sj.ijir.3901552.

[25] VENTADOUR S, ATTAIX D. Mechanisms of skeletal muscle atrophy[J]. Current Opinion in Rheumatology, 2006, 18(6): 631-635.DOI:10.1097/01.bor.0000245731.25383.de.

[26] SHAVLAKADZE T, CHAI J, MALEY K, et al. A growth stimulus is needed for IGF-1 to induce skeletal muscle hypertrophy in vivo[J].Journal of Cell Science, 2010, 123(6): 960-971. DOI:10.1242/jcs.061119.

[27] WITKOWSKI S, LOVERING R M, SPANGENBURG E E. Highfrequency electrically stimulated skeletal muscle contractions increase p70s6k phosphorylation independent of known IGF-I sensitive signaling pathways[J]. FEBS Letters, 2010, 584(13): 2891-2895.DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2010.05.003.

[28] 刘雪云, 李高权, 徐守宇. 废用性肌萎缩的蛋白质合成和降解途径[J].中国运动医学杂志, 2013, 32(7): 654-657; 632.

[29] PARKINGTON J D, LEBRASSEUR N K, SIEBERT A P, et al.Contraction-mediated mTOR, p70S6k, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in aged skeletal muscle[J]. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2004, 97(1):243-248. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.01383.2003.

[30] FUNAI K, PARKINGTON J D, CARAMBULA S, et al. Ageassociated decrease in contraction-induced activation of downstream targets of Akt/mTor signaling in skeletal muscle[J]. American Journal of Physiology Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology,2006, 290(4): 1080-1086. DOI:10.1152/ajpregu.00277.2005.

[31] HADDAD F, ADAMS G R. Aging-sensitive cellular and molecular mechanisms associated with skeletal muscle hypertrophy[J]. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2006, 100(4): 1188-1203. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.01227.2005.

[32] LÉGER B, DERAVE W, DE BOCK K, et al. Human sarcopenia reveals an increase in SOCS-3 and myostatin and a reduced efficiency of Akt phosphorylation[J]. Rejuvenation Research, 2008, 11(1): 163-175. DOI:10.1089/rej.2007.0588.

[33] RAHNERT J A, LUO Q, BALOG E M, et al. Changes in growthrelated kinases in head, neck and limb muscles with age[J]. Experimental Gerontology, 2011, 46(4): 282-291. DOI:10.1016/j.exger.2010.11.004.

[34] BODINE S C, LATRES E, BAUMHUETER S, et al. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy[J]. Science,2001, 294: 1704-1708. DOI:10.1126/science.1065874.

[35] SANDRI M, SANDRI C, GILBERT A, et al. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy[J]. Cell, 2004, 117(3): 399-412.

[36] CAI D S, FRANTZ J D, TAWA N E, et al. IKKbeta/NF-kappaB activation causes severe muscle wasting in mice[J]. Cell, 2004, 119(2):285-298. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.027.

[37] NEUFELD T P. TOR-dependent control of autophagy: biting the hand that feeds[J]. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 2010, 22(2): 157-168.DOI:10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.005.

[38] CHEONG H, YORIMITSU T, REGGIORI F, et al. Atg17 regulates the magnitude of the autophagic response[J]. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 2005, 16(7): 3438-3453. DOI:10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0894.

[39] PAPACKOVA Z, CAHOVA M. Important role of autophagy in regulation of metabolic processes in health, disease and aging[J].Physiological Research, 2014, 63(4): 409-420.

[40] WOHLGEMUTH S E, SEO A Y, MARZETTI E, et al. Skeletal muscle autophagy and apoptosis during aging: effects of calorie restriction and life-long exercise[J]. Experimental Gerontology, 2010,45(2): 138-148. DOI:10.1016/j.exger.2009.11.002.

[41] WENZ T, ROSSI S G, ROTUNDO R L, et al. Increased muscle PGC-1alpha expression protects from sarcopenia and metabolic disease during aging[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106(48): 20405-20410. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0911570106.

[42] WOLFE R R. The underappreciated role of muscle in health and disease[J]. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2006, 84(3): 475-482.

[43] DEFRONZO R A, TRIPATHY D. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2009,32(Suppl 2): S157-S163. DOI:10.2337/dc09-S302.

[44] JESSEN N, GOODYEAR L J. Contraction signaling to glucose transport in skeletal muscle[J]. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2005,99(1): 330-337. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00175.2005.

[45] HABETS D D J, LUIKEN J J F P, OUWENS M, et al. Involvement of atypical protein kinase C in the regulation of cardiac glucose and long-chain fatty acid uptake[J]. Frontiers in Physiology, 2012, 3: 1-8.DOI:10.3389/fphys.2012.00361.

[46] CLEASBY M E, JAMIESON P M, ATHERTON P J. Insulin resistance and sarcopenia: mechanistic links between common comorbidities[J]. Journal of Endocrinology, 2016, 229(2): 67-81.DOI:10.1530/JOE-15-0533.

[47] CHIBALIN A V, YU M, RYDER J W, et al. Exercise-induced changes in expression and activity of proteins involved in insulin signal transduction in skeletal muscle: differential effects on insulinreceptor substrates 1 and 2[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2000, 97(1): 38-43.

[48] KROOK A, WALLBERG-HENRIKSSON H, ZIERATH J R. Sending the signal: molecular mechanisms regulating glucose uptake[J].Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 2004, 36(7): 1212-1217.

[49] CHRIST C Y, HUNT D, HANCOCK J, et al. Exercise training improves muscle insulin resistance but not insulin receptor signaling in obese Zucker rats[J]. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2002, 92(2):736-744. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00784.2001.

[50] NICKLAS B J, CHMELO E, DELBONO O, et al. Effects of resistance training with and without caloric restriction on physical function and mobility in overweight and obese older adults: a randomized controlled trial[J]. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2015, 101(5):991-999. DOI:10.3945/ajcn.114.105270.

[51] KOSEK D J, KIM J S, PETRELLA J K, et al. Efficacy of 3 days/wk resistance training on myofiber hypertrophy and myogenic mechanisms in young vs. older adults[J]. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2006,101(2): 531-544. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.01474.2005.

[52] PAHOR M, BLAIR S N, ESPELAND M, et al. Effects of a physical activity intervention on measures of physical performance: results of the lifestyle interventions and independence for elders pilot (LIFE-P)study[J]. Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 2007, 62(3): 1157-1165.

[53] DAVIDSON L E, HUDSON R, KILPATRICK K, et al. Effects of exercise modality on insulin resistance and functional limitation in older adults: a randomized controlled trial[J]. Archives of Internal Medicine, 2009, 169(2): 122-131. DOI:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.558.

[54] 卢健. 骨骼肌衰减症与运动干预研究进展[J]. 体育科研, 2015, 36(3):1-7. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-1207.2015.03.001.

[55] 余群, 翁锡全, 王丽平. 骨骼肌减少症与运动训练对肌卫星细胞影响的研究现状及展望[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2016, 20(15): 2248-2254. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.2016.15.017.

[56] ZANCHI N E, DE SIQUEIRA F M A, LIRA F S, et al. Chronic resistance training decreases MuRF-1 and Atrogin-1 gene expression but does not modify Akt, GSK-3beta and p70S6K levels in rats[J].European Journal of Applied Physiology, 2009, 106(3): 415-423.DOI:10.1007/s00421-009-1033-6.

[57] PITHON-CURI T C, RODRIGUES C F, DE SOUSA L G O, et al.Effect of glutamine supplementation and resistive training in signaling pathways of protein synthesis and degradation in rat skeletal muscle[C]// Experimental Biology. Boston, USA: American Association of Anatomists, 2013.

[58] GOISSER S, KEMMLER W, PORZEL S, et al. Sarcopenic obesity and complex interventions with nutrition and exercise in communitydwelling older persons: a narrative review[J]. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 2015, 10: 1267-1282. DOI:10.2147/CIA.S82454.

[59] HAN T S, TAJAR A, LEAN M E. Obesity and weight management in the elderly[J]. British Medical Bulletin, 2011, 97: 169-196.DOI:10.1093/bmb/ldr002.

[60] MATHUS-VLIEGEN E M. Obesity and the elderly[J]. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 2012, 46(7): 533-544. DOI:10.1097/MCG.0b013e31825692ce.

[61] FITZPATRICK A L, KULLER L H, LOPEZ O L, et al. Midlife and late-life obesity and the risk of dementia: cardiovascular health study[J]. Archives of Neurology, 2009, 66(3): 336-342. DOI:10.1001/archneurol.2008.582.

[62] VILLAREAL D T, APOVIAN C M, KUSHNER R F, et al. Obesity in older adults: technical review and position statement of the American Society for Nutrition and NAASO, The Obesity Society[J]. Obesity Research, 2005, 13(11): 1849-1863. DOI:10.1038/oby.2005.228.

[63] BOUCHONVILLE M F, VILLAREAL D T. Sarcopenic obesity:how do we treat it?[J]. Current Opinion in Endocrinology,Diabetes, and Obesity, 2013, 20(5): 412-419. DOI:10.1097/01.med.0000433071.11466.7f.

[64] KOHARA K. Sarcopenic obesity in aging population: current status and future directions for research[J]. Endocrine, 2014, 45(1): 15-25.DOI:10.1007/s12020-013-9992-0.

[65] PRADO C M, WELLS J C, SMITH S R, et al. Sarcopenic obesity: a critical appraisal of the current evidence[J]. Clinical Nutrition, 2012,31(5): 583-601. DOI:10.1016/j.clnu.2012.06.010.

[66] PARR E B, COFFEY V G, HAWLEY J A. ‘Sarcobesity’: a metabolic conundrum[J]. Maturitas, 2013, 74(2): 109-113. DOI:10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.10.014.

[67] CETIN D C, NASR G. Obesity in the elderly: more complicated than you think[J]. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 2014, 81(1): 51-61.DOI:10.3949/ccjm.81a.12165.

[68] WATERS D L, WARD A L, VILLAREAL D T. Weight loss in obese adults 65 years and older: a review of the controversy[J].Experimental Gerontology, 2013, 48(10): 1054-1061. DOI:10.1016/j.exger.2013.02.005.

[69] MATHUS-VLIEGEN E M H, BASDEVANT A, FINER N, et al.Prevalence, pathophysiology, health consequences and treatment options of obesity in the elderly: a guideliner[J]. Obesity Facts, 2012,5(3): 460-483. DOI:10.1159/000341193.

[70] BISCHOFF-FERRARI H. Vitamin D: what is an adequate vitamin D level and how much supplementation is necessary?[J] Best Practice &Research: Clinical Rheumatology, 2009, 23(6): 789-795. DOI:10.1016/j.berh.2009.09.005.

[71] HOUSTON D K, TOOZE J A, HAUSMAN D B, et al. Change in 25-hydroxyvitamin D and physical performance in older adults[J].Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 2011, 66(4): 430-436. DOI:10.1093/gerona/glq235.

[72] CEGLIA L. Vitamin D and its role in skeletal muscle[J]. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 2009, 12(6): 628-633. DOI:10.1097/MCO.0b013e328331c707.

[73] CIPRIANI C, PEPE J, PIEMONTE S, et al. Vitamin D and its relationship with obesity and muscle[J]. International Journal of Endocrinology, 2014, 2014: 1-11. DOI:10.1155/2014/841248.

[74] MITHAL A, BONJOUR J P, BOONEN S, et al. Impact of nutrition on muscle mass, strength, and performance in older adults[J]. Osteoporosis International, 2013, 24(5): 1555-1566. DOI:10.1007/s00198-012-2236-y.

[75] FULLER J C, BAIER S, FLAKOLL P, et al. Vitamin D status affects strength gains in older adults supplemented with a combination of beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate, arginine, and lysine: a cohort study[J]. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 2011, 35(6): 757-762. DOI:10.1177/0148607111413903.

[76] ALLEY D E, KOSTER A, MACKEY D, et al. Hospitalization and change in body composition and strength in a population-based cohort of older persons[J]. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2010,58(11): 2085-2091. DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03144.x.

[77] GOTSHALK L A, KRAEMER W J, MENDONCA M A G, et al.Creatine supplementation improves muscular performance in older women[J]. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 2008, 102(2):223-231. DOI:10.1007/s00421-007-0580-y.

[78] DEVRIES M C, PHILLIPS S M. Creatine supplementation during resistance training in older adults-a meta-analysis[J]. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 2014, 46(6): 1194-1203. DOI:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000220.

[79] GUALANO B, RAWSON E S, CANDOW D G, et al. Creatine supplementation in the aging population: effects on skeletal muscle, bone and brain[J]. Amino Acids, 2016, 48(8): 1793-1805.DOI:10.1007/s00726-016-2239-7.

[80] BAUER J M, VERLAAN S, BAUTMANS I, et al. Effects of a vitamin D and leucine-enriched whey protein nutritional supplement on measures of sarcopenia in older adults, the providestudy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial[J]. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 2015, 16(9): 740-747.DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2015.05.021.

[81] BELL K E, SNIJDERS T, ZULYNIAK M, et al. A whey protein-based multi-ingredient nutritional supplement stimulates gains in lean body mass and strength in healthy older men: a randomized controlled trial[J]. PLoS ONE, 2017, 12(7): 1-18. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0181387.

Exercise and Nutrition Interventions of Sarcopenic Obesity and Underlying Mechanisms

XU Lei1,LI Chunyan2,CHEN Ning2,*,FAN Jingjing2,*

(1. Graduate School, Wuhan Sports University, Wuhan 430079, China; 2. Tianjiu Research and Development Center for Exercise Nutrition and Foods, College of Health Science, Wuhan Sports University, Wuhan 430079, China)

Abstract:Sarcopenic obesity (SO) is a progressive disease characterized by obesity accompanied by declining skeletal muscle mass and/or strength in aging populations, which seriously affects the quality of life of patients. A large number of studies have shown that the body composition of the elderly could gradually change with age, even if the body weight remains at the same level, skeletal muscle mass and functions could decrease and fat deposition could increase mainly in muscle tissues and visceral organs, leading to increased accumulation of intramuscular fat, accelerated secretion of inflammatory phenomena, reduced level of growth hormones, deficient intake of nutrients, increased daily physical inactivity,degenerated neuronal function, and improved insulin resistance, which are highly associated with sarcopenic obesity. Based on the molecular underlying molecular mechanisms, protein synthesis and degradation, glucose and lipid metabolism and related cytokines in skeletal muscle are involved in the regulation of skeletal muscle metabolism during sarcopenic obesity.Exercise intervention, calorie restriction, and consumption of proteins, vitamin D, β-hydroxy-β-methyl-butyrate (HMB),creatine and whey protein can play an important role in the prevention and treatment of sarcopenic obesity. Although the number of population with sarcopenic obesity increases, the pathogenesis of sarcopenic obesity is inconsistently understood and inconsistent evaluation criteria and prevention and treatment strategies for this disease are used by researchers, causing great difficulties in studying sarcopenic obesity. In this article, we summarize and discuss the literature to date regarding the definition, pathogenesis and related signal pathways of sarcopenic obesity, as well as the corresponding prevention and treatment strategies (exercise or nutrition interventions), which will provide a novel insight into the prevention and treatment of sarcopenic obesity.

Key words:sarcopenic obesity; pathogenesis; signal pathway; prevention and treatment strategies

收稿日期:2017-06-30

基金项目:国家自然科学基金面上项目(31571228);国家体育总局科教司科学研究项目(2014B093);湖北省高等学校优秀中青年科技创新团队项目(T201624);湖北省体育教育与健康促进学科群项目

作者简介:徐磊(1994—),男,硕士研究生,研究方向为运动与营养干预对慢性疾病康复。E-mail:924822285@qq.com

*通信作者:陈宁(1972—),男,教授,博士,研究方向为运动与营养干预对慢性疾病预防与康复。E-mail:nchen510@gmail.com范晶晶(1984—),女,讲师,博士,研究方向为运动与营养干预对慢性疾病预防与康复。E-mail:jie_jing_1@163.com

DOI:10.7506/spkx1002-6630-201721044

中图分类号:R151.4

文献标志码:A

文章编号:1002-6630(2017)21-0279-08

引文格式:徐磊, 李春艳, 陈宁, 等. 老年人肌少性肥胖的机制与运动营养调控研究进展[J]. 食品科学, 2017, 38(21): 279-286.

DOI:10.7506/spkx1002-6630-201721044. http://www.spkx.net.cn

XU Lei, LI Chunyan, CHEN Ning, et al. Exercise and nutrition interventions of sarcopenic obesity and underlying mechanisms[J]. Food Science, 2017, 38(21): 279-286. (in Chinese with English abstract) DOI:10.7506/spkx1002-6630-201721044. http://www.spkx.net.cn