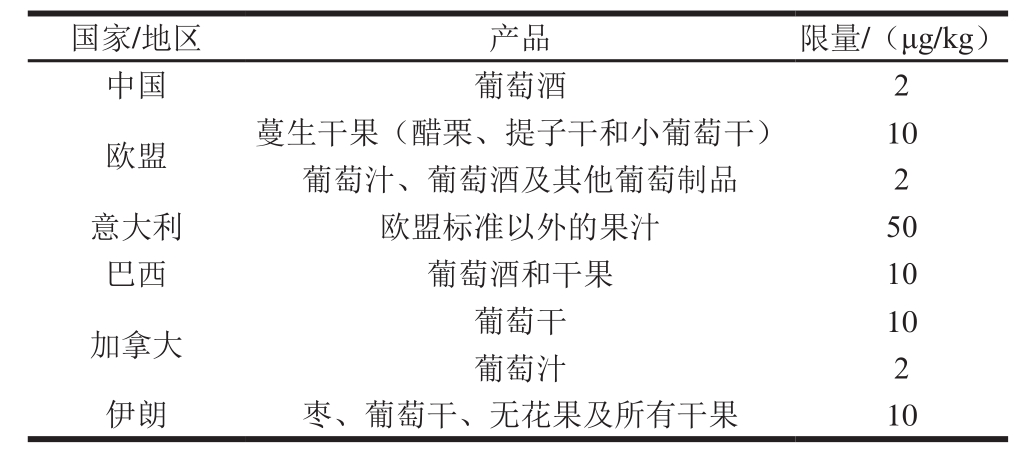

表1 国际组织和各国制定的果品及其制品中OTA限量标准[11]

Table1 Maximum limits for OTA in fruits, nuts and related products in different organizations and countries[11]

?

赭曲霉毒素A(ochratoxin A,OTA)是主要由曲霉属和青霉属真菌产生的毒性次生代谢产物,广泛污染多种农产品,包括谷物、葡萄、坚果、咖啡、可可和香辛料等。OTA的主要靶器官是肾脏,可引起肾中毒;另外,OTA还具有致癌性、肝毒性、基因毒性、细胞毒性、免疫毒性等[1]。国际癌症研究机构(International Agency of Research on Cancer,IARC)将其归为2B类致癌物[2]。OTA化学结构在酸性或高温条件下极其稳定,食物烹饪过程中仅部分结构分解,即使高压蒸汽灭菌(121 ℃)处理3 h也不能被完全破坏[3-4],这造成该毒素污染很难去除[1]。目前,大多数的研究集中在谷物及其制品中OTA的污染发生及其控制,而对水果、坚果及其制品中OTA污染现状的研究较少。本文综述了目前国内外果品及其制品中OTA的生物合成、检测技术、污染现状和控制等方面的研究进展,以期为今后果品及其制品中OTA污染的风险监测和控制提供理论参考。

OTA(分子式:C20H18ClNO6;分子质量:403.8 Da),即7-羧-5-氯-8-羟-3,4-二氢-3-R-甲基异香豆素-7-L-β-苯丙氨酸,由氯化的异香豆素类似物和苯丙氨酸以酰胺键连接而成,是一种白色、无味、热稳定的固体结晶物,其熔点约168~173 ℃。OTA水溶性差,可溶于碳酸氢钠溶液,易溶于醇、酮和氯仿等有机溶剂。

OTA首先发现于巴尔干地区,巴尔干流行性肾病以及与其相关的尿路肿瘤与OTA的污染密切相关[5]。巴尔干流行性肾病是一种慢性进行性疾病,长时间(6~10 年)患病可能导致不可逆的肾衰竭[6]。另外,OTA也被认为是突尼斯肾病[7]的主因。OTA致毒机理可能是:1)抑制苯丙氨酸-tRNA合成酶活性,进而抑制蛋白质的合成;2)引起线粒体功能异常,进而抑制细胞的能量代谢;3)OTA引起的氧化胁迫是其具有致癌性、基因毒性和细胞毒性等的重要原因[6,8]。

表1 国际组织和各国制定的果品及其制品中OTA限量标准[11]

Table1 Maximum limits for OTA in fruits, nuts and related products in different organizations and countries[11]

?

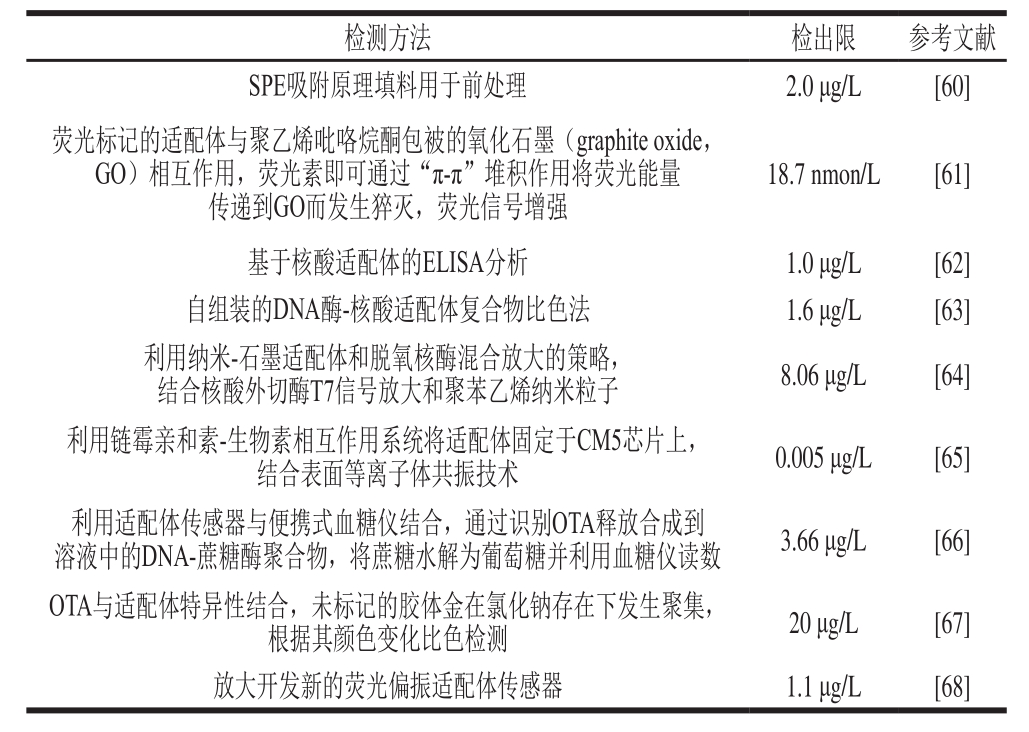

鉴于OTA的毒性强、污染广泛和稳定不易去除的特点,许多国家或组织均制定了食品中OTA限量标准,其中果品中OTA限量如表1所示。联合国粮食及农业组织和世界卫生组织下的食品添加剂联合专家委员会提出OTA的临时每周耐受摄入量为100 ng/kg mb[9],而欧盟提出的每日耐受摄入量为5 ng/kg mb[10]。由表1可以看出,OTA主要污染葡萄及其制品,这也许是意大利对欧盟标准(葡萄及其制品)以外的果汁限量相对宽松的原因之一。另外,各个国家或组织间OTA的限量标准、针对的果品种类差异较大,这可能与各国果品加工水平以及国民饮食文化有着密切的关系,相信随着产业的进步,各国对不同果品及其制品中OTA的限量规定会逐渐详细并愈加严格,这有利于保障人民的健康饮食。

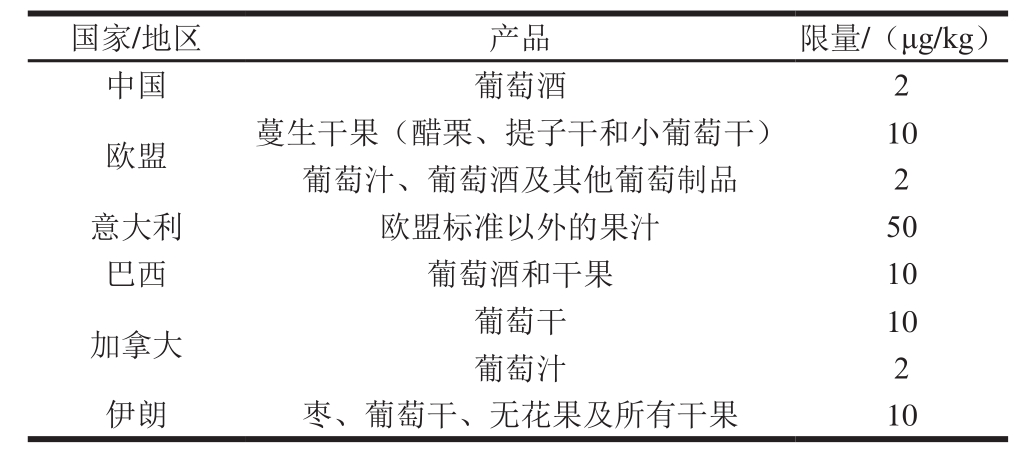

由OTA化学结构可以看出,其是由含氯元素的异香豆素衍生物——赭曲霉毒素α(ochratoxin α,OTα),即7-羧-5-氯-8-羟-3,4-二氢-R-甲基异香豆素和L-β-苯丙氨酸经酰胺键缩合而成。OTA是一种聚酮化合物,该类化合物的生物合成与脂肪酸合成类似,由乙酸等短链羧酸经聚酮合酶(polyketide synthase,PKS)催化多步聚酮缩合反应而成。早在1979年,Huff等根据OTA化学结构和鉴定出的OTA的结构类似物,预测了OTA的生物合成途径:以乙酰辅酶A为底物,经多步聚酮反应合成蜂蜜曲菌素,蜂蜜曲菌素经氧化生成赭曲霉毒素β(ochratoxin β,OTβ),而后被卤素化为OTα,接着OTα和苯丙氨酸乙酯合成赭曲霉毒素C(ochratoxin C,OTC),最终经脱乙酯键合成OTA[12]。其中,中间产物OTC和苯丙氨酸乙酯的形成主要是为了保护苯丙氨酸的羧基。而2001年,Harris等根据同位素标记的底物饲喂实验,结合赭曲霉中OTA相关代谢物的变化,推测该毒素的生物合成主要是通过OTβ→OTα→OTA途径,另外还有可能存在替代途径:OTβ→赭曲霉毒素B(ochratoxin B,OTB)→OTA[13]。然而,并未检出OTC参与OTA的生物合成。2012年,Gallo及其同事通过对炭黑曲霉中非核糖体多肽合成酶(non-ribosomal peptide synthetases,NRPS)基因的敲除以及与野生型比较OTA合成过程中的潜在中间产物变化,最终预测了一条OTA的生物合成途径:乙酰辅酶A经多步聚酮反应首先合成OTβ,再与另一底物苯丙氨酸经NRPS催化缩合生成OTB,OTB经氯代过氧化物酶/卤化酶的作用最终合成OTA[14]。另外,Gallo等还推测前人研究中的潜在中间产物OTα可能是OTA经水解而成的副产物[14]。2016年,Ferrara等[15]通过对炭黑曲霉基因组中潜在参与OTA合成的卤化酶基因的敲除,进一步证实了OTA由卤化酶催化加氯而合成。另外,Ferrara等还推测OTβ不仅是OTA合成的中间产物,而且在炭黑曲霉中可能存在水解反应将OTB水解为OTβ(图1)。

近年来,对OTA生物合成的分子机制研究多集中在pks基因中,研究人员对OTA主要产生菌——赭曲霉[16-17]、Aspergillus westerdijkiae[18]、炭黑曲霉[19]、黑曲霉[20]、疣梗青霉[21]、Penicillium nordicum[22]中潜在参与OTA生物合成的pks基因进行了分析,并通过基因敲除技术进行功能验证,分别确证了相应pks基因参与OTA的生物合成。而酰胺键的形成是由NRPS催化酰胺缩合反应而成,Gallo等[14]揭示了炭黑曲霉中参与OTA合成的nrps基因AcOTAnrps的功能。Karolewiez[22]、Färber[23]和Gerin[24]等分别通过对OTA产毒菌P. nordicum和炭黑曲霉的基因差异表达分析,推测卤化酶基因参与OTA的生物合成。此外,Ferrara等通过基因敲除和代谢产物分析进一步证实了炭黑曲霉中卤化酶基因AcOTAhal参与OTA的生物合成,确认该酶催化OTB加氯合成OTA[15]。另外,P450单加氧酶基因(P450)可能参与OTA生物合成。Sartori等对A. westerdijkiae进行基因差异表达分析,分析OTA产毒菌和非产毒菌,发现其中P450基因在产毒菌中表达显著较高,推测该基因可能参与A. westerdijkiae中OTA的合成[25]。Gil-Serna等通过对Aspergillus steynii基因组步移和基因差异表达分析,预测与潜在参与OTA合成的pks基因pksste和nrps基因nrpsste相邻的P450基因p450ste可能参与A. steynii中OTA的生物合成[26]。Ferrara等同样发现了位于AcOTAhal基因附近的可能参与OTA合成的P450基因AcOTAp450[15]。然而,推测潜在参与OTA合成的P450基因功能仍待进一步确证。

图1 OTA生物合成途径预测图[14-15]

Fig.1 Schematic diagram of the putative OTA biosynthetic pathway[14-15]

随着分子技术的进步与发展,人们对OTA产生菌的基因组的认识逐渐深入,对于参与OTA生物合成的基因功能也渐渐被揭示。虽然近年来对OTA生物合成途径的研究已经解析出了该毒素合成的部分遗传背景,但是在OTA的合成过程中所参与的合成酶和中间产物的时空顺序尚不明确,相信在不久的将来,该合成途径及其分子基础将被充分揭示,这也将为OTA的监测和防控提供更加坚实的依据。

果品及其制品中OTA污染的及时发现有助于对毒素污染的果品及其制品快速有效地加以应对,有助于保障果品的质量安全,降低居民膳食暴露风险。因此,OTA检测技术是明确果品及其制品中OTA污染状况的前提和关键。目前,果品及其制品中OTA污染的检测技术主要有:薄层色谱(thin-layer chromatography,TLC)、高效液相色谱(high performance liquid chromatography,HPLC)、HPLC-串联质谱(HPLC-tandem mass spectrum,HPLC-MS/MS)技术和基于抗原、抗体或核酸适配体的快速检测技术等。

TLC是最早用于真菌毒素污染检测和监测的色谱分析方法,由于其具有操作简单、价格低廉等优点,目前在一些发展中国家仍作为常规技术手段用于毒素检测。然而,由于TLC检测的灵敏度较低,实验步骤较繁琐,期间所用溶剂毒性较大,而且还存在干扰较强、重现性较差等缺点,难以满足OTA检测的需求。TLC结合其他一些技术设备能够有效地提高检测效率和灵敏度,如TLC结合新型电荷耦合检测器已被应用于红酒中OTA检测,OTA定量限可低至0.8 μg/L[27]。此外,结合光密度法的高效TLC、二维TLC及超压TLC也能较好地减少分析时间并提高分析结果的准确度和精密度。

OTA具有紫外吸收官能团,而且能够产生荧光,较常采用荧光检测器(fluorometric detector,FLD)进行检测。HPLC与紫外检测器(ultraviolet detector,UVD)、FLD等结合使用,高效、稳定而又快速的样品前处理是保障检测结果准确有效的前提。目前常用的样品前处理措施有液-液萃取法、固相萃取(solid-phase extraction,SPE)技术、QuEChERs(quick, easy, cheap,effective, rugged and safe)技术、免疫亲和层析净化(immunoaffinity cleanup,IAC)技术等。SPE技术由于具有简单、快速、高效、环境污染少等优点,目前已被大量应用于真菌毒素提取之中。QuEChERs技术原理与SPE相似,它具有快速、高效、简便、安全、溶剂用量少等优点,现已广泛应用于毒素检测的前处理之中。基于免疫学的IAC技术由于其对所提取物质特异性强的特点也越来越多地应用于果品及其制品的样品前处理中,成为OTA的HPLC-FLD检测的主要前处理方法。OTA利用FLD检测均采用333 nm激发荧光,而发射波长有所不同(433~477 nm),因为OTA的荧光特性受OTA所处微环境的影响,即使同样在333 nm激发波长处,不同pH值、溶剂等条件下,其最强发射波长也有所不同[28-29](表2)。

表 2 果品及其制品中OTA的HPLC-FLD检测

Table2 Determination of OTA in fruits, nuts and related products using HPLC-FLD

注:LOD.检测限;VA-EME-SFOD.基于漂浮有机液滴固化的漩涡辅助乳化微萃取。

?

近年来,随着MS技术的发展,作为灵敏度高、可靠性好的HPLC-MS/MS技术越来越多地应用于果品及其制品OTA污染的检测中。而且HPLC-MS/MS技术还具有能够同时检测多种毒素等优点。应用HPLC-MS/MS检测OTA的前处理方法较多,包括SPE、QuEChERs、IAC和稀释进样等(表3)。其中,稀释进样的回收率波动范围较大,应探索应用更加有效的萃取方法。

表 3 果品及其制品中OTA的HPLC-MS/MS检测

Table3 Determination of OTA in fruits, nuts and related products using HPLC-MS/MS

?

相对于TLC和HPLC检测,免疫化学法具有前处理简单、特异性强、快速、灵敏等优点,特别适合大规模检测,已越来越广泛地应用于真菌毒素检测。目前应用于果品及其制品中OTA检测的免疫化学检测技术主要包括酶联免疫吸附测定(enzymelinked immunosorbent assay,ELISA)、免疫层析法(immunochromatography,IC)和荧光免疫分析法(fluoroimmunoassay,FIA)等。

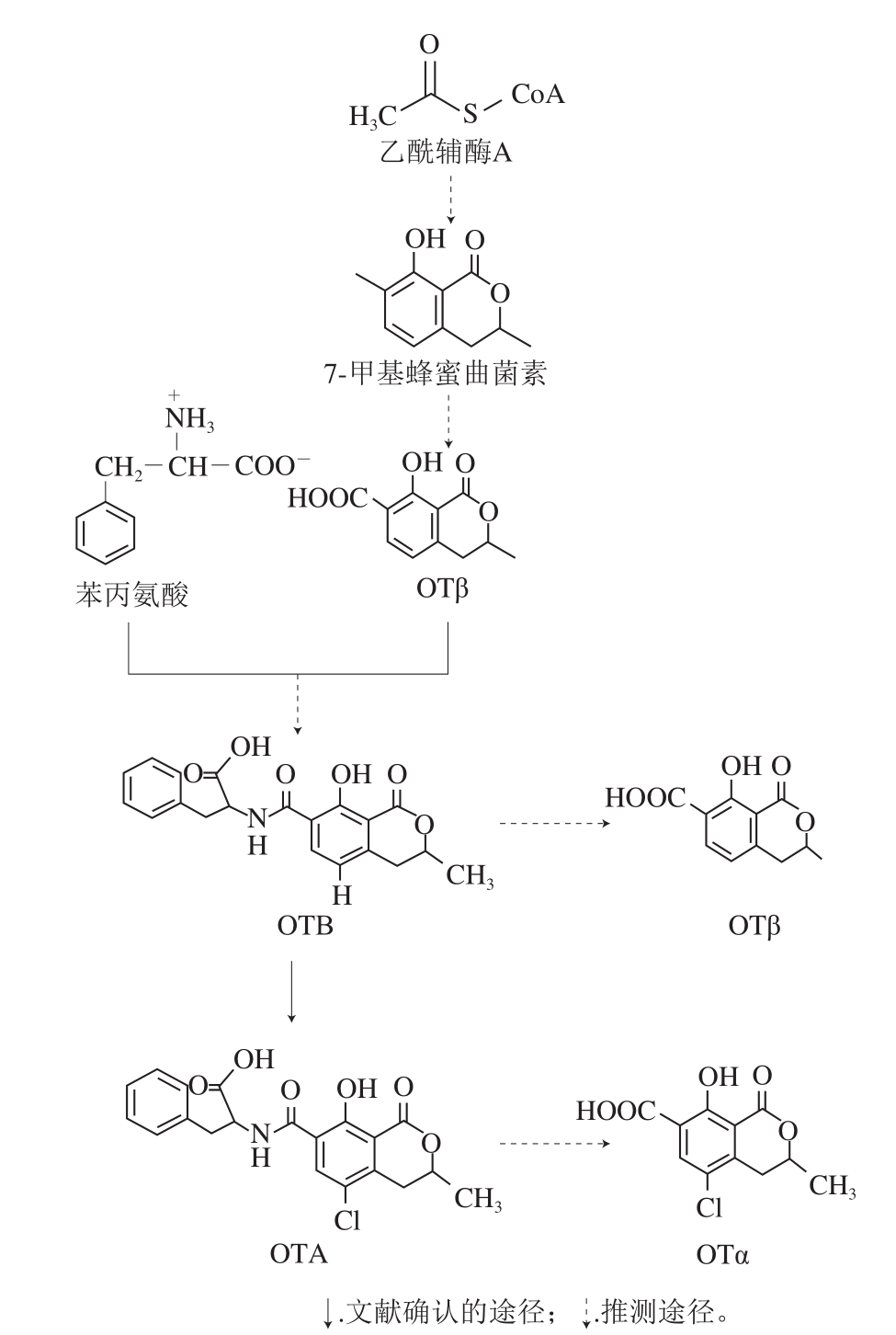

ELISA是将抗原、抗体的高度特异性和酶的高效催化相结合的一种免疫化学检测方法,其检测原理是待测样本经处理与酶标抗原/抗体发生免疫反应,经洗涤去除非特异性结合,通过酶催化反应的分析来映射待检样本中特定化合物,对其进行定量检测与分析,可分为夹心和竞争两种检测模式。由于OTA为小分子半抗原,通常采用竞争反应模式,包括直接竞争、间接竞争和非竞争3 种方式。Pavón等利用直接竞争法检测无花果干中的OTA含量,检出限可达3.2 μg/kg(表4)[54]。抗体和OTA反应的特异性是检测结果准确性的关键,而抗体与其结构类似物OTB、OTC存在交叉反应,待测样品中的OTB、OTC等结构类似物的存在可能会影响结果的准确性。另外,待测样品中的其他成分如酚类物质也会干扰ELISA法检测果品中OTA的结果。开心果中的酚类物质可能与抗体发生交叉反应造成假阳性,基于ELISA法检测OTA的试剂盒与总酚、没食子酸、儿茶素和表儿茶素的相关性很高(相关系数分别为0.757、0.732、0.729和0.590)[55]。ELSIA中的酶具有一般蛋白质共有的特点,易受到环境因素的影响,这也可能会影响检测结果。

表4 果品及其制品中OTA的免疫化学检测

Table4 Immunochemical detection of OTA in fruits, nuts and related products

?

IC技术是基于单克隆抗体、胶体金免疫和新材料技术发展起来的一种新型快速筛查方法,其中以胶体金作为示踪标记物的胶体金IC测定具有灵敏度高、特异性强、稳定性好、操作简便等优点,且不受仪器设备限制,结果判断直观可靠,适用于大批量样品的现场快速检测。虽然目前这种方法还只能半定量,但作为一种快速筛查手段,可有效筛除毒素污染的农产品,进而保护人们的身体健康。以胶体金作为标记物检测葡萄干和葡萄汁中的OTA已有报道[56]。随着新材料的应用,金包银纳米粒子[57]、量子点[58]可作为抗体标记应用于葡萄酒中OTA污染的快速检测。

FIA基于荧光标记技术,通过检测荧光信号强弱对OTA结果进行判定。荧光检测相对普通吸光度检测灵敏度更高,能够对特殊靶标进行微量甚至超微量检测。已有报道应用荧光偏振免疫分析(fluorescence polarization immunoassay,FPIA)检测果品及其制品中的OTA。Zezza等[59]建立了基于单克隆抗体和OTA荧光素示踪剂的FPIA技术,并将其应用于葡萄酒中OTA的检测。OTA质量浓度为2.0、5.0 µg/L,平均回收率为79%,检测限为0.7 µg/L。天然污染或加标情况下,该方法检测结果与HPLC法的相关性高达0.922,说明该方法有效且可靠。

核酸适配体是体外人工筛选获得的由约20~60 个碱基组成的具有特异性识别功能的单链DNA或RNA片段。除了具有单克隆抗体的高亲和性和特异性的特点外,其还具有可体外筛选、可化学合成或改造、分子质量小、靶分子范围广、可逆变性复性、可通过酶扩增或剪切和无免疫原性和毒性等优点。对于OTA来说,获得高亲和的适配体序列是目前研究的热点和关键。基于核酸适配体检测葡萄酒中的OTA已有诸多报道(表5),通过与多种信号放大系统的结合,其检测限越来越符合检测需求。将基于核酸适配体的葡萄酒中OTA快速检测技术延展至其他不同果品及其制品中加以应有也是目前需要关注的重点。

表5 基于核酸适配体检测葡萄酒中的OTA

Table5 Determination of OTA in red wine based on nucleic acid aptamer

?

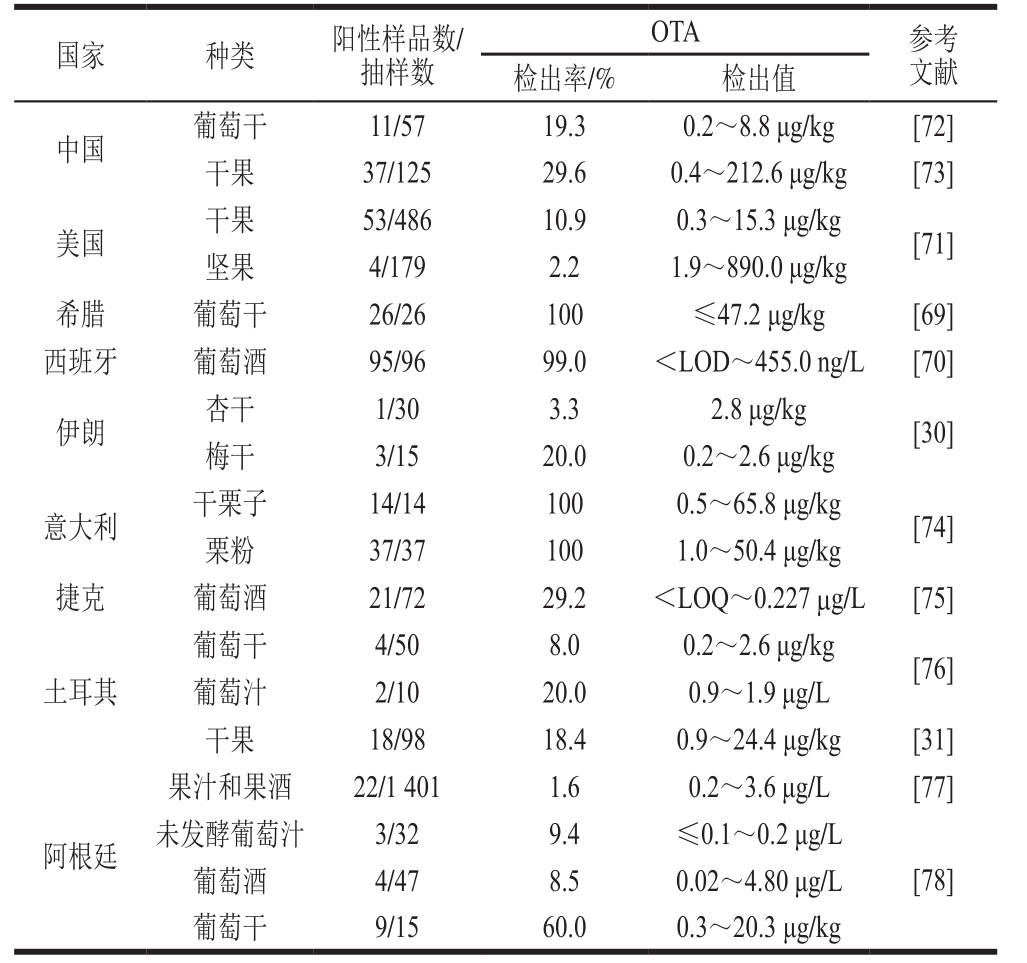

由近10 年(2007年以来)来果品及其制品中OTA污染报道可看出,葡萄干、葡萄汁、葡萄酒等葡萄制品的污染比较严重,另外,在栗子等坚果中也发现了OTA污染。在希腊市售葡萄干中OTA检出率甚至高达100%,其含量最高可达47.2 µg/kg,远超欧盟限量标准(10.0 µg/kg)[69]。在西班牙和阿根廷的葡萄酒中均有OTA检出,在西班牙的葡萄酒中其检出率甚至高达99%,质量浓度最高达455 µg/L[70]。除葡萄及其制品外,在一些坚果及其制品中OTA污染也较严重。2012—2014年,对美国7 个州超市内的干果和坚果产品的OTA污染情况进行分析,发现665 个样品中有57 个检出OTA污染,其中有2 个葡萄干和1 个开心果样品OTA含量超过10 µg/kg,开心果样品OTA含量最高甚至达890 µg/kg[71](表6)。

表6 果品及其制品中OTA污染状况(自2007年以来)

Table6 Contamination status of OTA in fruits, nuts and related products (since 2007)

注:LOQ.定量限。

?

据欧盟食品和饲料类快速预警系统统计:自2007年以来,OTA污染水果和蔬菜类产品的通告多达167 例,我国有2 例OTA污染严重,分别是葡萄干和甘草根,其中葡萄干的OTA含量高达20.7 µg/kg;而在坚果、坚果制品和种子类目下OTA污染的通告较少,有20 例,我国出口的相关商品发现6 例污染严重,除了1 例烤花生(含量高达33 µg/kg)外,其他5 例均是南瓜子;另外,在红葡萄酒的检测中发现有2 例OTA污染比较严重,分别为3.5 µg/L和2.42 µg/kg。

尽管对果品中OTA的污染状况已有较深入的认识,但是对OTA的膳食暴露风险评估研究仍在摸索之中。OTA的风险评估同样包括危害识别、危害描述、暴露评估和风险描述4 个方面,其中暴露评估是其核心[79-80]。现阶段,OTA膳食暴露风险评估多是根据消费者饮食消费数据和OTA的污染水平估算膳食摄入量的点评估,以及基于RISK软件分析的概率评估推导出居民膳食摄入水平,通过与OTA毒理学分析得出的每日耐受摄入量等人类健康指导值比较,用以评估人们的膳食暴露风险[79,81]。杨家玲对我国主要食品中OTA进行风险评估,利用OTA含量平均值进行暴露评估,得到安全限值为94%,表明OTA对食品安全影响的风险可以接受,而其中坚果的OTA平均暴露量远低于大米、面及面制品、豆类等粮油食品[79]。Han Zheng等通过点评估和蒙特卡洛评估模型对我国上海市成年居民膳食暴露风险的评估结果表明,除谷物及其制品外,葡萄及其制品、干果及其制品等食品暴露风险极低[80]。Mitchell等研究美国食品中OTA的膳食暴露风险,结果显示膳食暴露风险最高的人群是婴幼儿和儿童,而总体上OTA污染风险可以忽略不计[81]。总之,在果品及其制品中,除了高风险人群(婴幼儿和儿童)、少量高污染水平的样品等,其他多数情况下OTA污染风险很低,不会对人们的饮食健康造成威胁[11,79-82]。结合高风险人群和果品中葡萄及其制品污染率和污染水平较高的情况,OTA膳食暴露风险应重点关注葡萄及其制品消费量大的地区的人群,尤其是婴幼儿和儿童。果品及其制品中OTA的膳食暴露风险评估的深入研究将有助于针对不同果品种类、不同人群的OTA限量标准的制订。

由于果品及其制品中产毒真菌侵染的普遍性和真菌毒素产生的高发生,OTA污染的风险控制至关重要。果品及其制品中OTA的污染控制,一方面是产毒真菌的防控,另一方面是真菌毒素污染的控制和去除,两者密不可分。果品采前控制措施、采后处理方法和良好的贮藏条件对产毒真菌的生长及其毒素污染的风险控制十分重要。科学的果品作物耕种管理、良好的采前栽培措施和对危害分析和关键控制点的有效控制,以及采收、贮藏、运输以及加工等环节的科学处理能够降低果品OTA的污染风险。果品及其制品中OTA污染的控制策略分为物理、化学和生物3 类方法,对果品OTA污染的控制不仅能够挽回巨大的经济损失,而且能够使人们享用品质优良的产品,有效地保障人们身体健康。

果品及其制品中OTA污染的物理控制主要包括机械分选、清洗、热处理、射线、吸附等。机械分选、清洗和热处理等传统的果品防控方法长期用于防止产毒真菌的侵染和定植,能够在果品生产、加工等阶段减小其携带产毒菌的可能性。近年来,在果品中真菌毒素污染的控制方面也逐渐发展出新的物理控制方法,如射线、吸附等。

射线照射防控果品及其制品中OTA污染的研究主要集中在紫外线照射和γ射线辐照方面。紫外线照射能够显著抑制炭黑曲霉在以葡萄和开心果为基质的培养基上的生长和定植以及毒素的积累,其对OTA的抑制率甚至在80%以上[83]。不同的紫外线照射条件对不同的OTA产生菌菌株生长和毒素积累效果各异,但总体上紫外-A(320~400 nm,辐照能量峰值在365 nm波长处)对不同炭黑曲霉菌株及其OTA积累的控制效果要优于紫外-B(280~370 nm,辐照能量峰值在312 nm波长处),炭黑曲霉318-UdLTA对紫外线更敏感。此外,紫外线不仅能抑制产毒菌产毒,还可降解OTA,而环境条件能够影响紫外线对OTA的降解效率。对葡萄汁中OTA的紫外照射表明,pH 7时的降解效果优于pH 4时,说明中性条件下紫外线处理效果较佳[84]。温度也会影响紫外处理果品中OTA的效果。将温度由15 ℃升高至65 ℃,同样条件下进行紫外照射处理,OTA抑制率由约45%上升至67%。γ射线辐照不仅能够杀死产毒真菌、降低果品采后的腐烂损失,而且能够降解果品中的OTA。经10 kGy γ射线辐照处理的炭黑曲霉污染的葡萄干,贮藏12 d后仍未检测出OTA[85]。辐照剂量、真菌毒素的初始浓度、pH值等均会影响γ射线对OTA的降解作用[86]。较低初始浓度的OTA降解率较高,在碱性条件下的降解效果优于中性和酸性条件。60Co-γ射线辐照剂量越大越利于其降解[86-87]。湿度升高能够增强γ射线对OTA的降解能力[87]。

物理吸附也是一种有效脱除果品中OTA的方式。活性炭、沸石、硅藻土等物理吸附剂可用于OTA等多种真菌毒素的脱毒。蒙脱石和壳聚糖微球能吸附去除葡萄酒中60%~100%的OTA,特别是蒙脱石效果较佳,且对葡萄酒特性破坏很小,很少吸收其中的多酚和花青素等有益成分[88]。

果品及其制品中OTA污染的化学控制主要包括杀菌剂和消毒剂的使用。嘧菌环胺、咯菌腈、苯氧威等化学杀菌剂可以防控果园中炭黑曲霉等产毒真菌对葡萄的侵染以及OTA的积累[89-91]。但采前杀菌剂的长期使用会导致真菌抗性的不断积累,防控效果越来越差。另外,随着人们对公众健康的日益关注,采后杀菌剂的使用越来越受到限制,甚至被禁止使用。消毒剂一般在加工或销售前,结合清洗或热处理等操作对水果进行表面消毒,能够有效抑制产毒真菌在水果表面的定植。消毒剂中的臭氧由于其高效、对品质影响小、适用于加工过程以及环境友好等优点被广泛关注。早在2004年,美国食品和药品监督管理局建议苹果汁和苹果酒生产中使用臭氧消毒以降低病原菌的侵染。有研究发现,臭氧不仅能够有效地控制赭曲霉、炭黑曲霉等OTA产生菌的生长,抑制孢子的萌发[92-93],还能有效地降解OTA[94]。

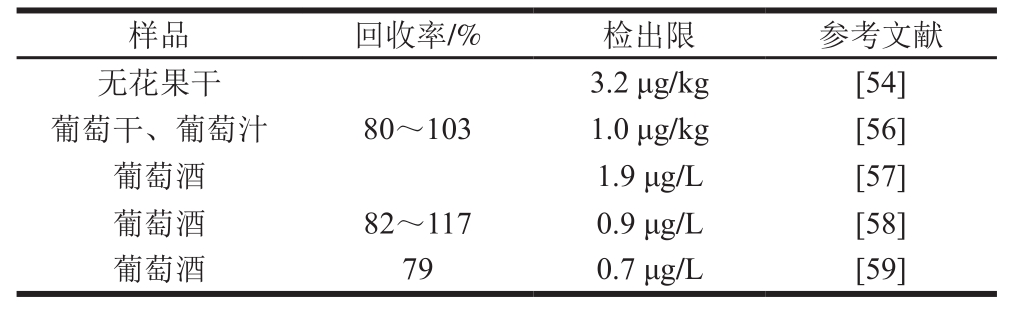

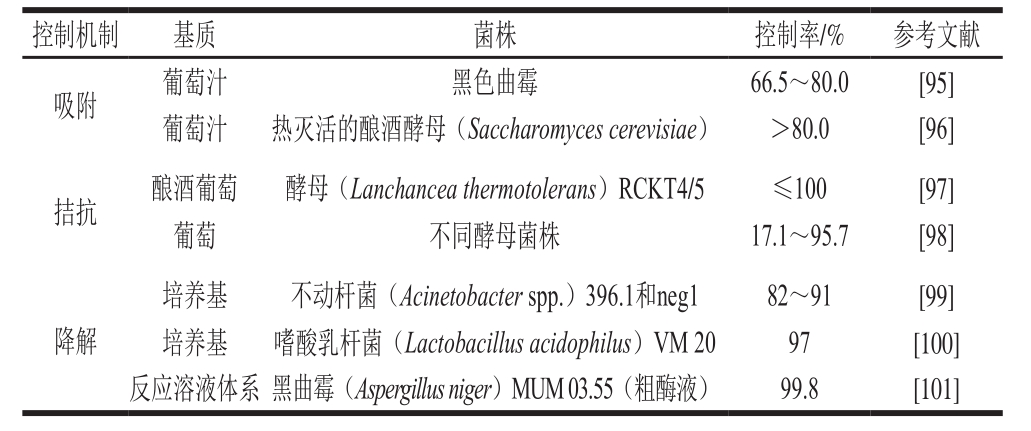

果品及其制品中OTA污染的生物控制主要包括微生物对OTA的吸附作用、拮抗微生物抑制产毒菌及其毒素的积累和微生物对OTA的降解作用。酵母和黑色曲霉均对OTA具有吸附作用,其对OTA的吸附脱除作用可能与其细胞壁的糖类物质(葡聚糖、甘露聚糖、壳聚糖等)有关。拮抗微生物主要通过抑制产毒真菌的生长进而抑制OTA的积累。研究发现有多种细菌和真菌能够降解OTA。对不同微生物体内OTA降解机制的研究表明,OTA的生物降解主要是通过断裂酰胺键,将OTA水解成L-β-苯丙氨酸和基本无毒的OTα实现的[99-101](表7)。

表7 果品及其制品中OTA污染的微生物控制

Table7 Microbiological control of OTA contamination in fruits, nuts and related products

?

水果、坚果及其制品是我国重要的食用消费品,而OTA是主要污染果品及其制品的真菌毒素之一。本文综述了OTA的生物合成、果品及其制品中OTA检测技术、污染状况与控制等内容。OTA生物合成途径的逐渐揭示为将来探索针对OTA合成过程中的关键酶或基因的阻控技术和产品提供了可能,而如何快速、高效地探寻出针对特定靶标酶或基因的阻控技术和产品成为其中的重点和难点。对果品及其制品中OTA污染状况的准确认识和对暴露风险的有效评估均离不开毒素检测技术的发展,然而利用HPLC-MS/MS等仪器的OTA检测有时间相对滞后的缺点,难以对果品及其制品进行现场检测分析。因此,对果品及其制品的快速、高效、高灵敏度而又经济实用的现场检测技术,尤其是基于抗原、抗体和核酸适配体的快速检测技术的开发与应用是未来关键的发展方向。无论是大型仪器检测还是快速检测,快速、高效的前处理技术的运用都是保证OTA提取率、减少损失、避免杂质干扰的重要手段。在果品及其制品中OTA污染的控制方面,抑制产毒菌的侵染是OTA污染防控的关键之一,除抗性品种的栽培和科学的田间管理外,化学杀菌剂和消毒剂的使用是重要的抑菌措施。化学残留的问题一直困扰着生产者和消费者,而生物控制具有环境友好的优点,因此采取化学和生物控制相结合的方法,开发高效、低毒的杀菌剂、消毒剂和环境友好的拮抗微生物产品能够更好地避免产毒真菌侵入果树体内,减少果品携带产毒菌的可能性。此外,对污染果品中OTA的降解去除也是果品及其制品中OTA污染控制的重要组成部分,其中射线辐照和臭氧处理是降解OTA重要的理化方法,然而射线和臭氧不具有专一性,可能破坏果品及其制品的营养品质,因此射线和臭氧剂量等条件的优化必须以保证其营养品质为前提。另外,微生物及其产生的解毒酶对OTA的降解具有反应温和、专一性强的特点,因此探索降解OTA的微生物资源和研发专一、高效的生物降解酶制剂等产品也是今后OTA防控应重点关注的领域。

[1] EL KHOURY A E, ATOUI A. Ochratoxin A: general overview and actual molecular status[J]. Toxins, 2010, 2(4): 461-493. DOI:10.3390/toxins2040461.

[2] International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Some naturally occurring substances, food items and constituents, heterocyclic aromatic amines and mycotoxins. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, vol. 56[M]. Lyon: IARC, 1993: 23.

[3] TRIVEDI A B, DOI E, KITABATAKE N. Detoxification of ochratoxin A on heating under acidic and alkaline conditions[J]. Bioscience Biotechnology and Biochemistry, 1992, 56(5): 741-745. DOI:10.1271/bbb.56.741.

[4] BOUDRA H, LE B P, LE B J. Thermostability of ochratoxin A in wheat under two moisture conditions[J]. Applied & Environmental Microbiology, 1995, 61(3): 1156-1158.

[5] ZHAO L N, PENG Y P, ZHANG X Y, et al. Integration of transcriptome and proteome data reveals ochratoxin A biosynthesis regulated by pH in Penicillium citrinum[J]. RSC Advances, 2017, 7:46767-46777. DOI:10.1039/C7RA06927H.

[6] KŐSZEGI T, POÓR M. Ochratoxin A: molecular interactions,mechanisms of toxicity and prevention at the molecular level[J].Toxins, 2016, 8(4): 1-25. DOI:10.3390/toxins8040111.

[7] HASSEN W, ABID-ESSAFI S, ACHOUR A, et al. Karyomegaly of tubular kidney cells in human chronic interstitial nephropathy in Tunisia: respective role of ochratoxin A and possible genetic predisposition[J]. Human & Experimental Toxicology, 2004, 23(7):339-346. DOI:10.1191/0960327104ht458oa.

[8] TAO Y B, XIE S Y, XU F F, et al. Ochratoxin A: toxicity, oxidative stress and metabolism[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2018, 112:320-331. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2018.01.002.

[9] PFOHL-LESZKOWICZ A, MANDERVILLE R A. Ochratoxin A: an overview on toxicity and carcinogenicity in animals and humans[J]. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 2007, 51(1): 61-99.DOI:10.1002/mnfr.200600137.

[10] 李楠, 江涛, 张宏元, 等. 北京地区啤酒中赭曲霉毒素A污染调查及暴露评估[J]. 中国食品卫生杂志, 2010, 22(3): 271-274.DOI:10.13590/j.cjfh.2010.03.003.

[11] 李志霞, 聂继云, 闫震, 等. 果品主要真菌毒素污染检测、风险评估与控制研究进展[J]. 中国农业科学, 2017, 50(2): 332-347.DOI:10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2017.02.012.

[12] HUFF W E, HAMILTON P B. Mycotoxins-their biosynthesis in fungi:ochratoxins-metabolites of combined pathways[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 1979(10): 815-820.

[13] HARRIS J P, MANTLE P G. Biosynthesis of ochratoxins by Aspergillus ochraceus[J]. Phytochemistry, 2001, 58(5): 709-716.DOI:10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00316-8.

[14] GALLO A, BRUNO K S, SOLFRIZZO M, et al. New insight into the ochratoxin A biosynthetic pathway through deletion of a nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene in Aspergillus carbonarius[J]. Applied &Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 78(23): 8208-8218. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02508-12.

[15] FERRARA M, PERRONE G, GAMBACORTA L, et al. Identification of a halogenase involved in the biosynthesis of ochratoxin A in Aspergillus carbonarius[J]. Applied & Environmental Microbiology,2016, 82(18): 5631-5641. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01209-16.

[16] O’CALLAGHAN J, CADDICK M X, DOBSON A D. A polyketide synthase gene required for ochratoxin A biosynthesis in Aspergillus ochraceus[J]. Microbiology, 2003, 149(12): 3485-3491. DOI:10.1099/mic.0.26619-0.

[17] WANG L Q, WANG Y, WANG Q, et al. Functional characterization of new polyketide synthase genes involved in ochratoxin A biosynthesis in Aspergillus ochraceus fc-1[J]. Toxins, 2015, 7(8): 2723-2738.DOI:10.3390/toxins7082723.

[18] BACHA N, ATOUI A, MATHIEU F, et al. Aspergillus westerdijkiae polyketide synthase gene “aoks1” is involved in the biosynthesis of ochratoxin A[J]. Fungal Genetics and Biology, 2009, 46(1): 77-84.DOI:10.1016/j.fgb.2008.09.015.

[19] GALLO A, KNOX B P, BRUNO K S, et al. Identification and characterization of the polyketide synthase involved in ochratoxin A biosynthesis in Aspergillus carbonarius[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2014, 179(5): 10-17. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.03.013.

[20] ZHANG J, ZHU L Y, CHEN H Y, et al. A polyketide synthase encoded by the gene An15g07920 is involved in the biosynthesis of ochratoxin A in Aspergillus niger[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2016, 64(51): 9680-9688. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.6b03907.

[21] ABBAS A, COGHLAN A, O’CALLAGHAN J, et al. Functional characterization of the polyketide synthase gene required for ochratoxin A biosynthesis in Penicillium verrucosum[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2013, 161(3): 172-181. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.12.014.

[22] KAROLEWIEZ A, GEISEN R. Cloning a part of the ochratoxin A biosynthetic gene cluster of Penicillium nordicum and characterization of the ochratoxin polyketide synthase gene[J]. Systematic &Applied Microbiology, 2005, 28(7): 588-595. DOI:10.1016/j.syapm.2005.03.008.

[23] FÄRBER P, GEISEN R. Analysis of differentially-expressed ochratoxin A biosynthesis genes of Penicillium nordicum[J]. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 2004, 110(5/6): 661-669. DOI:10.1023/B:EJPP.0000032405.21833.89.

[24] GERIN D, ANGELINI R M D M, POLLASTRO S, et al. RNASeq reveals OTA-related gene transcriptional changes in Aspergillus carbonarius[J]. PLoS ONE, 2016, 11(1): 1-21. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0147089.

[25] SARTORI D, MASSI F P, FERRANTI L S, et al. Identification of genes differentially expressed between ochratoxin-producing and nonproducing strains of Aspergillus westerdijkiae[J]. Indian Journal of Microbiology, 2014, 54(1): 41-45. DOI:10.1007/s12088-013-0408-x.

[26] GIL-SERNA J, VÁZQUEZ C, GONZÁLEZ-JAÉN M T, et al.Clustered array of ochratoxin A biosynthetic genes in Aspergillus steynii and their expression patterns in permissive conditions[J].International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2015, 214: 102-108.DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.07.020.

[27] TEIXEIRA T R, HOELTZ M, EINLOFT T C, et al. Determination of ochratoxin A in wine from the southern region of Brazil by thin layer chromatography with a charge-coupled detector[J]. Food Additives and Contaminants: Part B, 2011, 4(4): 289-293. DOI:10.1080/1939321 0.2011.638088.

[28] HASHEMI J, ALIZADEH N. Investigation of solvent effect and cyclodextrins on fluorescence properties of ochratoxin A[J]. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2009, 73(1): 121-126. DOI:10.1016/j.saa.2009.02.001.

[29] ORTEGA S J, APPELL M D, WANG L C, et al. Effect of pH and solvent on the fluorescence spectroscopy of ochratoxin A[Z]. Peoria,Illinois: 2016.

[30] JANATI S S F, BEHESHTI H R, ASADI M, et al. Preliminary survey of aflatoxins and ochratoxin A in dried fruits from Iran[J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination & Toxicology, 2012, 88(3): 391-395.DOI:10.1007/s00128-011-0477-7.

[31] BIRCAN C. Incidence of ochratoxin A in dried fruits and co-occurrence with aflatoxins in dried figs[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2009, 47(8): 1996-2001. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2009.05.008.

[32] TERRA M F, PRADO G, PEREIRA G E, et al. Detection of ochratoxin A in tropical wine and grape juice from Brazil[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2013, 93(4): 890-894. DOI:10.1002/jsfa.5817.

[33] FEIZY J, BEHESHTI H R, ASADI M. Ochratoxin A and aflatoxins in dried vine fruits from the Iranian market[J]. Mycotoxin Research,2012, 28(4): 237-242. DOI:10.1007/s12550-012-0145-8.

[34] SOLFRIZZO M, PIEMONTESE L, GAMBACORTA L, et al.Food coloring agents and plant food supplements derived from Vitis vinifera: a new source of human exposure to ochratoxin A[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2015, 63(13): 3609-3614.DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b00326.

[35] FANELLI F, COZZI G, RAIOLA A, et al. Raisins and currants as conventional nutraceuticals in Italian market: natural occurrence of ochratoxin A[J]. Journal of Food Science, 2017, 82(10): 2306-2312.DOI:10.1111/1750-3841.13854.

[36] SOLFRIZZO M, PANZARINI G, VISCONTI A. Determination of ochratoxin A in grapes, dried vine fruits, and winery byproducts by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorometric detection(HPLC-FLD) and immunoaffinity cleanup[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2008, 56(23): 11081-11086. DOI:10.1021/jf802380d.

[37] KUANG Y, QIU F, KONG W J, et al. Natural occurrence of ochratoxin A in wolfberry fruit wine marketed in China[J]. Food Additives and Contaminants: Part B, 2012, 5(1): 70-74. DOI:10.1080/19393210.2012.660198.

[38] MELETIS K, MENIADES-MEIMAROGLOU S, MARKAKI P.Determination of ochratoxin A in grapes of Greek origin by immunoaffinity and high-performance liquid chromatography[J].Food Additives and Contaminants, 2007, 24(11): 1275-1282.DOI:10.1080/02652030701413852.

[39] HESHMATI A, MOZAFFARI N A S. Ochratoxin A in dried grapes in Hamadan province, Iran[J]. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part B,2015, 8(4): 255-259. DOI:10.1080/19393210.2015.1074945.

[40] ZINEDINE A, SORIANO J M, JUAN C, et al. Incidence of ochratoxin A in rice and dried fruits from Rabat and Salé area,Morocco[J]. Food Additives and Contaminants, 2007, 24(3): 285-291.DOI:10.1080/02652030600967230.

[41] PAVÓN M Á, GONZÁLEZ I, DE L C S, et al. The use of highperformance liquid chromatography to detect ochratoxin A in dried figs from the Spanish market[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2012, 92(1): 74-77. DOI:10.1002/jsfa.4543.

[42] ZAIED C, ABID S, BOUAZIZ C, et al. Ochratoxin A levels in spices and dried nuts consumed in Tunisia[J]. Food Additives and Contaminants: Part B, 2010, 3(1): 52-57.DOI:10.1080/19440041003587302.

[43] HESHMATI A, ZOHREVAND T, KHANEGHAH A M, et al.Co-occurrence of aflatoxins and ochratoxin A in dried fruits in Iran:dietary exposure risk assessment[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology,2017, 106: 202-208. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2017.05.046.

[44] ZHANG X X, LI J M, ZONG N, et al. Ochratoxin A in dried vine fruits from Chinese markets[J]. Food Additives and Contaminants:Part B, 2014, 7(3): 157-161. DOI:10.1080/19393210.2013.867365.

[45] ASADI M. Determination of ochratoxin A in fruit juice by highperformance liquid chromatography after vortex-assisted emulsification microextraction based on solidification of floating organic drop[J].Mycotoxin Research, 2017, 34(1): 15-20. DOI:10.1007/s12550-017-0294-x.

[46] ARROYO-MANZANARES N, HUERTAS-PÉREZ J F, GÁMIZGRACIA L, et al. A new approach in sample treatment combined with UHPLC-MS/MS for the determination of multiclass mycotoxins in edible nuts and seeds[J]. Talanta, 2013, 115(17): 61-67. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2013.04.024.

[47] RUBERT J, SEBASTIÀ N, SORIANO J M, et al. One-year monitoring of aflatoxins and ochratoxin A in tiger-nuts and their beverages[J]. Food Chemistry, 2011, 127(2): 822-826. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.01.016.

[48] BELTRÁN E, IBÁÑEZ M, PORTOLÉS T, et al. Development of sensitive and rapid analytical methodology for food analysis of 18 mycotoxins included in a total diet study[J]. Analytica Chimica Acta,2013, 783(11): 39-48. DOI:10.1016/j.aca.2013.04.043.

[49] KOLAKOWSKI B, O’ROURKE S M, BIETLOT H P, et al.Ochratoxin A concentrations in a variety of grain-based and nongrain-based foods on the Canadian retail market from 2009 to 2014[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2016, 79(12): 2143-2159.DOI:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-16-051.

[50] ŠKRBIĆ B, ANTIĆ I, CVEJANOV J. Determination of mycotoxins in biscuits, dried fruits and fruit jams: an assessment of human exposure[J]. Food Additives and Contaminants: Part A-Chemistry,Analysis, Control, Exposure & Risk Assessment, 2017, 34(6): 1012-1025. DOI:10.1080/19440049.2017.1303195.

[51] ZHANG X, LI J M, CHENG Z, et al. High-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for simultaneous detection of ochratoxin A and relative metabolites in Aspergillus species and dried vine fruits[J]. Food Additives and Contaminants:Part A-Chemistry, Analysis, Control, Exposure & Risk Assessment,2016, 33(8): 1355-1366. DOI:10.1080/19440049.2016.1209691.

[52] ZHANG X X, OU X Q, ZHOU Z Y, et al. Ochratoxin A in Chinese dried jujube: method development and survey[J]. Food Additives and Contaminants: Part A-Chemistry, Analysis, Control, Exposure & Risk Assessment, 2015, 32(4): 512-517. DOI:10.1080/19440049.2014.976844.

[53] SPANJER M C, RENSEN P M, SCHOLTEN J M. LC-MS/MS multimethod for mycotoxins after single extraction, with validation data for peanut, pistachio, wheat, maize, cornflakes, raisins and figs[J].Food Additives and Contaminants: Part A-Chemistry, Analysis,Control, Exposure & Risk Assessment, 2008, 25(4): 472-489.DOI:10.1080/02652030701552964.

[54] PAVÓN M Á, GONZALEZ I, MARTIN R, et al. Competitive direct ELISA based on a monoclonal antibody for detection of ochratoxin A in dried fig samples[J]. Food and Agricultural Immunology, 2012,23(1): 83-91. DOI:10.1080/09540105.2011.604769.

[55] LEE H J, MELDRUM A D, RIVERA N, et al. Cross-reactivity of antibodies with phenolic compounds in pistachios during quantification of ochratoxin A by commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2014, 77(10): 1754-1759.DOI:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-189.

[56] WANG X H, LIU T, XU N, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and colloidal gold immunoassay for ochratoxin A: investigation of analytical conditions and sample matrix on assay performance[J].Analytical & Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2007, 389(3): 903-911.DOI:10.1007/s00216-007-1506-6.

[57] WANG L B, CHEN W, MA W W, et al. Fluorescent strip sensor for rapid determination of toxins[J]. Chemical Communications, 2011,47(5): 1574-1576. DOI:10.1039/c0cc04032k.

[58] ANFOSSI L, NARDO F D, GIOVANNOLI C, et al. Increased sensitivity of lateral flow immunoassay for ochratoxin A through silver enhancement[J]. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2013,405(30): 9859-9867. DOI:10.1007/s00216-013-7428-6.

[59] ZEZZA F, LONGOBARDI F, PASCALE M, et al. Fluorescence polarization immunoassay for rapid screening of ochratoxin A in red wine[J]. Analytical & Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2009, 395(5): 1317-1323. DOI:10.1007/s00216-009-2994-3.

[60] CHAPUIS-HUGON F, DU B A, MADRU B, et al. New extraction sorbent based on aptamers for the determination of ochratoxin A in red wine[J]. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2011, 400(5): 1199-1207. DOI:10.1007/s00216-010-4574-y.

[61] SHENG L, REN J, MIAO Y, et al. PVP-coated graphene oxide for selective determination of ochratoxin A via quenching fluorescence of free aptamer[J]. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 2011, 26(8): 3494-3499. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2011.01.032.

[62] BARTHELMEBS L, JONCA J, HAYAT A, et al. Enzyme-linked aptamer assays (ELAAs), based on a competition format for a rapid and sensitive detection of ochratoxin A in wine[J]. Food Control,2011, 22(5): 737-743. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2010.11.005.

[63] YANG C, LATES V, PRIETO-SIMÓN B, et al. Rapid high-throughput analysis of ochratoxin A by the self-assembly of DNAzyme-aptamer conjugates in wine[J]. Talanta, 2013, 116(22): 520-526. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2013.07.011.

[64] WEI Y, ZHANG J, WANG X, et al. Amplified fluorescent aptasensor through catalytic recycling for highly sensitive detection of ochratoxin A[J]. Biosensors & Bioelectronics, 2015, 65(65): 16-22. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2014.09.100.

[65] ZHU Z L, FENG M X, ZUO L M, et al. An aptamer based surface plasmon resonance biosensor for the detection of ochratoxin A in wine and peanut oil[J]. Biosensors & Bioelectronics, 2015, 65: 320-326.DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2014.10.059.

[66] GU C M, LONG F, ZHOU X H, et al. Portable detection of ochratoxin A in red wine based on a structure-switching aptamer using a personal glucometer[J]. RSC Advances, 2016, 6(35): 29563-29569.DOI:10.1039/C5RA27880E.

[67] YIN X T, WANG S, LIU X Y, et al. Aptamer-based colorimetric biosensing of ochratoxin A in fortified white grape wine sample using unmodified gold nanoparticles[J]. Analytical Sciences, 2017, 33(6):659-664. DOI:10.2116/analsci.33.659.

[68] SAMOKHVALOV A V, SAFENKOVA I V, EREMIN S A, et al. Use of anchor protein modules in fluorescence polarisation aptamer assay for ochratoxin A determination[J]. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2017, 962:80-87. DOI:10.1016/j.aca.2017.01.024.

[69] KOLLIA E, KANAPITSAS A, MARKAKI P. Occurrence of aflatoxin B1and ochratoxin A in dried vine fruits from Greek market[J]. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part B, 2014, 7(1): 11-16. DOI:10.1080/19 393210.2013.825647.

[70] REMIRO R, IRIGOYEN A, GONZÁLEZ-PEÑAS E, et al. Levels of ochratoxins in Mediterranean red wines[J]. Food Control, 2013, 32(1):63-68. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.11.040.

[71] PALUMBO J D, O’KEEFFE T L, HO Y S, et al. Occurrence of ochratoxin A contamination and detection of ochratoxigenic Aspergillus species in retail samples of dried fruits and nuts[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2015, 78(4): 836-842. DOI:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-471

[72] WEI D Z, WANG Y, JIANG D M, et al. Survey of Alternaria toxins and other mycotoxins in dried fruits in China[J]. Toxins, 2017, 9(7):1-12. DOI:10.3390/toxins9070200.

[73] HAN Z, DONG M F, HAN W, et al. Occurrence and exposure assessment of multiple mycotoxins in dried fruits based on liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry[J]. World Mycotoxin Journal, 2016, 9(3): 465-474. DOI:10.3920/WMJ2015.1983.

[74] PIETRI A, RASTELLI S, MULAZZI A, et al. Aflatoxins and ochratoxin A in dried chestnuts and chestnut flour produced in Italy[J]. Food Control, 2012, 25(2): 601-606. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.11.042.

[75] MIKULÍKOVÁ R, BĚLÁKOVÁ S, BENEŠOVÁ K, et al. Study of ochratoxin A content in South Moravian and foreign wines by the UPLC method with fluorescence detection[J]. Food Chemistry, 2012,133(1): 55-59. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.12.061.

[76] QUINTELA S, VILLARÁN M C, ARMENTIA L D I, et al.Occurrence of ochratoxin A in Rioja Alavesa wines[J]. Food Chemistry,2011, 126(1): 302-305. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.09.096.

[77] MOTEIZA J, KHANEGHAH A M, CAMPAGNOLLO F B, et al.Influence of production on the presence of patulin and ochratoxin A in fruit juices and wines of Argentina[J]. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 2017, 80: 200-207. DOI:10.1016/j.lwt.2017.02.025.

[78] PONSONE M L, CHIOTTA M L, COMBINA M, et al. Natural occurrence of ochratoxin A in musts, wines and grape vine fruits from grapes harvested in Argentina[J]. Toxins, 2010, 2(8): 1984-1996.DOI:10.3390/toxins2081984.

[79] 杨家玲. 我国主要食品中赭曲霉毒素A调查与风险评估[D]. 杨凌:西北农林科技大学, 2008: 15-44.

[80] HAN Zheng, NIE Dongxia, YANG Xianli, et al. Quantitative assessment of risk associated with dietary intake of mycotoxin ochratoxin A on the adult inhabitants in Shanghai city of P.R.China[J]. Food Control, 2013, 32(2): 490-495. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.01.031.

[81] MITCHELL N J, CHEN C, PALUMBO J D, et al. A risk assessment of dietary ochratoxin A in the United States[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2017, 100: 265-273. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2016.12.037.

[82] VAN DE PERRE E, JACXSENS L, LACHAT C, et al. Impact of maximum levels in European legislation on exposure of mycotoxins in dried products: case of aflatoxin B1and ochratoxin A in nuts and dried fruits[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2015, 75: 112-117.DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2014.10.021.

[83] GARCÍA-CELA E, MARIN S, SANCHIS V, et al. Effect of ultraviolet radiation A and B on growth and mycotoxin production by Aspergillus carbonarius and Aspergillus parasiticus in grape and pistachio media[J]. Fungal Biology, 2015, 119(1): 67-78. DOI:10.1016/j.funbio.2014.11.004.

[84] IBARZ R, GARVÍN A, AZUARA E, et al. Modelling of ochratoxin A photo-degradation by a UV multi-wavelength emitting lamp[J]. LWTFood Science and Technology, 2015, 61(2): 385-392. DOI:10.1016/j.lwt.2014.12.017.

[85] KANAPITSAS A, BATRINOU A, ARAVANTINOS A, et al. Gamma radiation inhibits the production of ochratoxin A by Aspergillus carbonarius. development of a method for OTA determination in raisins[J]. Food Bioscience, 2016, 15: 42-48. DOI:10.1016/j.fbio.2016.05.001.

[86] 彭春红, 周林燕, 李淑荣, 等.60Co-γ射线对赭曲霉毒素A辐照的降解效果[J]. 中国食品学报, 2015, 15(7): 174-179. DOI:10.16429/j.1009-7848.2015.07.025.

[87] KUMAR S, KUNWAR A, GAUTAM S, et al. Inactivation of A.ochraceus spores and detoxification of ochratoxin A in coffee beans by gamma irradiation[J]. Journal of Food Science, 2012, 77(2): T44-T51.DOI:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02572.x.

[88] KURTBAY H M, BEKÇI Z, MERDIVAN M, et al. Reduction of ochratoxin A levels in red wine by bentonite, modified bentonites, and chitosan[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2008, 56(7):2541-2545. DOI:10.1021/jf073419i.

[89] TJAMOS S E, ANTONIOU P P, KAZANTZIDOU A, et al. Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus carbonarius in Corinth raisin and wineproducing vineyards in Greece: population composition, ochratoxin A production and chemical control[J]. Journal of Phytopathology, 2010,152(4): 250-255. DOI:10.1111/j.1439-0434.2004.00838.x.

[90] KAPPES M, SERRATI L, DROUILLARD J, et al. A crop protection approach to Aspergillus and OTA management in Southern European vineyards[C]//Ochratoxin A in grapes and wine: prevention and control. Marsala: International Workshop, 2005: 8-9.

[91] BELLÍ N, MARÍN S, ARGILÉS E, et al. Effect of chemical treatments on ochratoxigenic fungi and common mycobiota of grapes (Vitis vinifera)[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2007, 70(1): 157-163.DOI:10.4315/0362-028X-70.1.157.

[92] FODIL S, YASEEN T, D ONGHIA A M, et al. Use of ozone to control conidial germination in ochratoxin A producing black Aspergilli isolated in raisins from Algeria[J]. Acta Horticulturae, 2016, 1144:163-168. DOI:10.17660/ActaHortic.2016.1144.23.

[93] IACUMIN L, MANZANO M, COMI G. Prevention of Aspergillus ochraceus growth on and ochratoxin A contamination of sausages using ozonated air[J]. Food Microbiology, 2012, 29(2): 229-232.DOI:10.1016/j.fm.2011.06.018.

[94] 邓捷, 陈文洁, 郭柏雪, 等. 臭氧降解玉米中赭曲霉毒素A的效果及对玉米脂肪酸的影响[J]. 食品科学, 2011, 32(21): 12-16.

[95] BEJAOUI H, MATHIEU F, TAILLANDIER P, et al. Conidia of black Aspergilli as new biological adsorbents for ochratoxin A in grape juices and musts[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2005,53(21): 8224-8229. DOI:10.1021/jf051029v.

[96] ABRUNHOSA L, SANTOS L, VENANCIO A. Degradation of ochratoxin A by proteases and by a crude enzyme of Aspergillus niger[J]. Food Biotechnology, 2006, 20(3): 231-242.DOI:10.1080/08905430600904369.

[97] DE BELLIS P, TRISTEZZA M, HAIDUKOWSKI M, et al.Biodegradation of ochratoxin A by bacterial strains isolated from vineyard soils[J]. Toxins, 2015, 7(12): 5079-5093. DOI:10.3390/toxins7124864.

[98] FARBO M G, URGEGHE P P, FIORI S, et al. Adsorption of ochratoxin A from grape juice by yeast cells immobilised in calcium alginate beads[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2016,217: 29-34. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.10.012.

[99] PONSONE M L, NALLY M C, CHIOTTA M L, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of potential biocontrol yeasts against black sur rot and ochratoxin A occurring under greenhouse and field grape production conditions[J]. Biological Control, 2016, 103: 78-85. DOI:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2016.07.012.

[100] PANTELIDES I S, CHRISTOU O, TSOLAKIDOU M D, et al.Isolation, identification and in vitro screening of grapevine yeasts for the control of black aspergilli on grapes[J]. Biological Control, 2015,88: 46-53. DOI:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2015.04.021.

[101] FUCHS S, SONTAG G, STIDL R, et al. Detoxification of patulin and ochratoxin A, two abundant mycotoxins, by lactic acid bacteria[J].Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2008, 46(4): 1398-1407. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2007.10.008.

Occurrence, Control and Determination of Ochratoxin A Contamination in Fruits, Nuts and Related Products