潜在食源性致病菌弓形菌在食品中的分布及检测研究进展

吴瑜凡1,王 翔2,崔思宇1,邵景东1,*

(1.张家港出入境检验检疫局检验检疫综合技术中心,江苏 张家港 215600;2.上海理工大学医疗器械与食品学院,上海 200093)

摘 要:弓形菌(Arcobacter spp.)是一类重要的食源性致病菌,因其与弯曲菌(Campylobacter spp.)形态相似且亲缘关系很近,最初被称为“氧气耐受的弯曲菌”。弓形菌属内能够引起人致病的主要是布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌和斯氏弓形菌,感染致病性的弓形菌可以引起人类的肠炎、严重腹泻、败血症和菌血症等。弓形菌广泛存在于畜禽、畜禽产品和环境中,畜禽产品生产设备和水源的污染是造成其高感染率的主要途径。由于弓形菌的生理特征与弯曲菌相近,分离培养时通常较难与弯曲菌区分,分子生物学方法是弓形菌实验室诊断的主要手段。近年来,作为新型潜在的食源性致病菌,弓形菌逐渐引起研究者的关注。然而,相较于其他食源性致病菌,对弓形菌的研究尚处于起步阶段,国内的报道也相对较少。本文对弓形菌在食品中的污染现状、流行病学特点及弓形菌的实验室检测等相关研究进展进行综述,以期为广大研究者提供有价值的信息。

关键词:弓形菌;食源性致病菌;分布;流行病学特征;实验室检测

弓形菌属(Arcobacter spp.)是一类新型的人畜共患的食源性和水源型病原菌,因其与弯曲菌形态相似且亲缘关系相近,最早被划分在弯曲菌属,称为“氧气耐受的弯曲菌”。1991年Vandamme等通过亲缘性比对,将其划分为独立的分支——弓形菌属[1]。目前弓形菌属内已发现和报道的有22 个种(http://www.bacterio.net/arcobacter.html),其中有10 种弓形菌分离于自然环境,如Arcobacter nitrofigilis分离自植物根际,具有固氮功能,最初被称为Campylobacter nitrogigilis[2],随后划入弓形菌属[1];另外12 种均分离自人源或动物源,其中最受关注的是布氏弓形菌(Arcobacter butzleri)、斯氏弓形菌(Arcobacter skirrowii)和嗜低温弓形菌(Arcobacter cryaerophilus),据报道这3 种菌与人类和动物的腹泻、菌血症等疾病密切相关。布氏弓形菌(Arcobacter butzleri)是最为常见的弓形菌属致病菌,可以引起人类的肠炎、严重腹泻、败血症和菌血症等[3]。2002年国际食品微生物标准委员会将弓形菌定为对人类健康有严重危害类微生物[4],2007年北欧食品分析委员会专家也针对弓形菌的现状和相关研究做了专项技术报告[5]。虽然针对弓形菌的报道逐年增加,然而相较于其他食源性致病菌,对弓形菌的研究尚处于起步阶段,国内对于该菌的报道也相对较少。本文对弓形菌在食品中的污染现状、流行病学特点及弓形菌的实验室检测等相关进展进行综述,以期为广大研究者提供有价值的信息。

1 弓形菌在食品中的分布

弓形菌在形态上与弯曲菌非常相似,都属于ε-变形菌纲。弓形菌通常大小为(1~3 μm)×(0.2~0.9 μm),呈弯曲状S形或螺旋形,革兰氏阴性,端生鞭毛,有运动性,在显微镜下可见其进行螺旋状翻滚或突进运动。在血琼脂上30 ℃好氧培养48~72 h后,长出直径为2~4 mm大小的灰白色圆形菌落[3]。多数菌株在液体培养基中只能观察到微弱的生长。弓形菌基因组DNA的G+C含量范围在27%~30%。虽然与弯曲菌属细菌亲缘关系较近且形态相似,但是其生长特性有明显差异,相较于弯曲菌,弓形菌具有更广的生长温度范围和更强的氧气耐受性,因而较弯曲菌更易存活。弓形菌可以在15~37 ℃的条件下生长,最适生长温度为30 ℃,较弯曲菌的最适生长温度(37~42 ℃)更低。另外,弓形菌最适生长环境为微好氧环境(氧气体积分数3%~10%),在正常有氧条件下和厌氧条件下均可生长[6]。因此,生长温度和氧气耐受性通常是鉴别弓形菌属和弯曲菌属的重要指标。

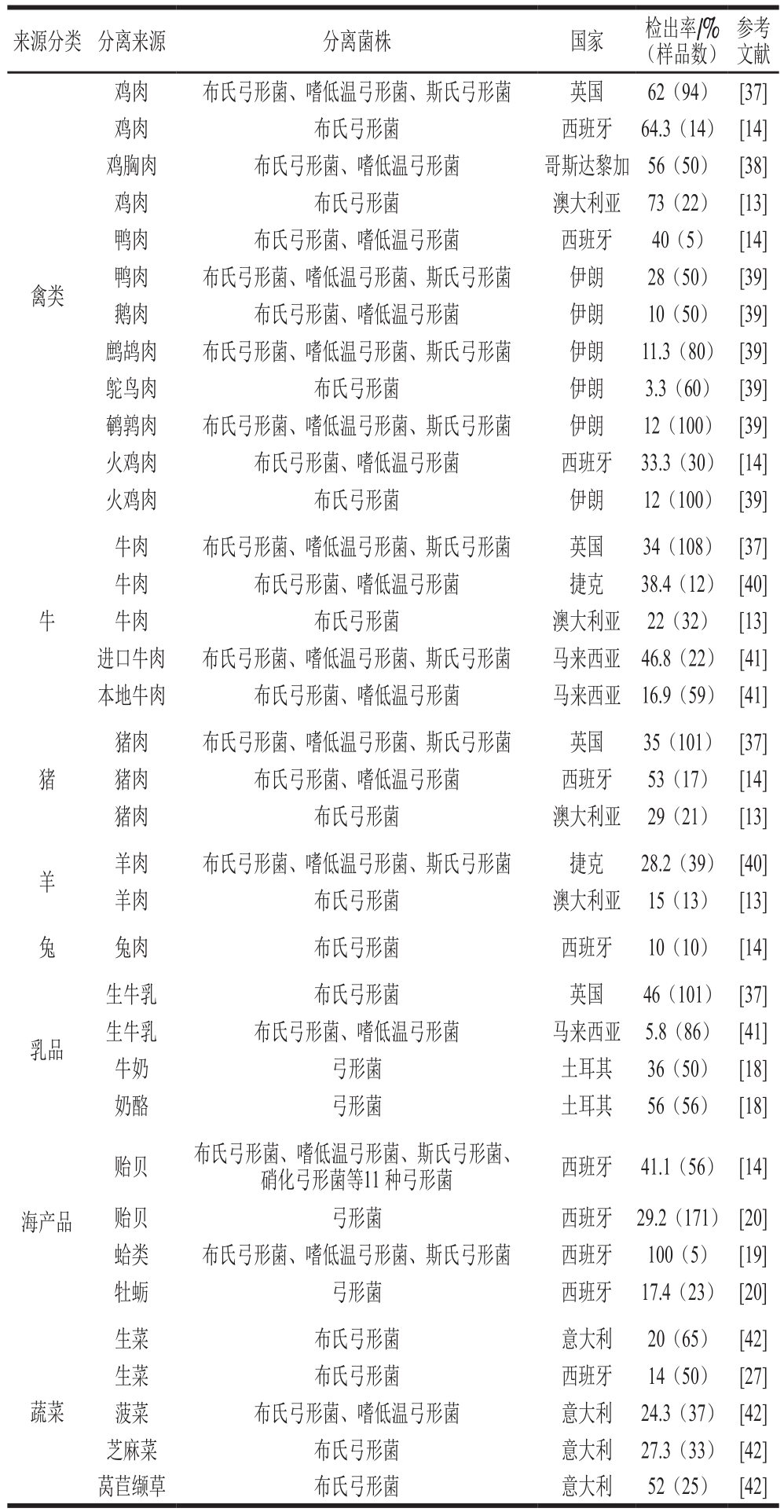

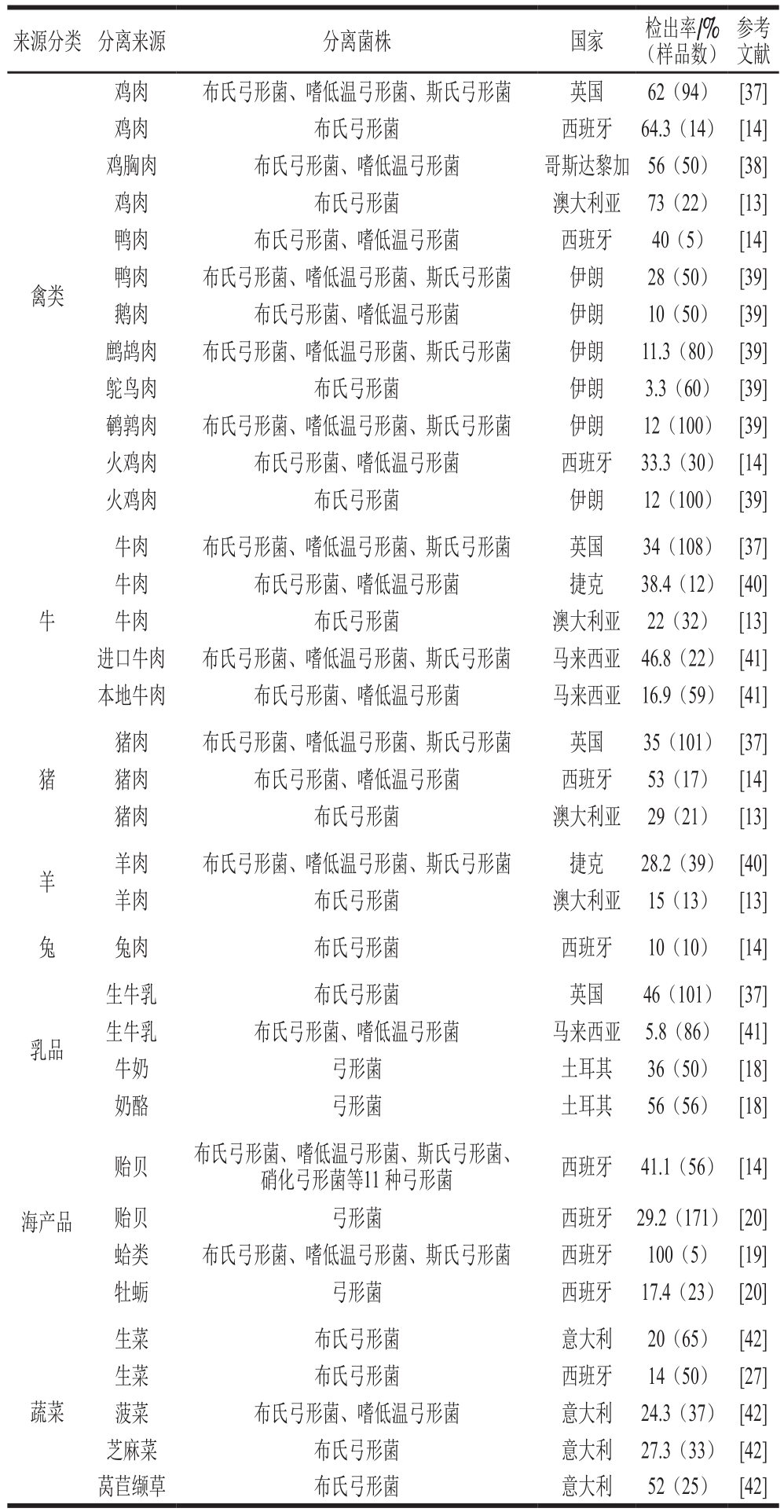

近年来,很多研究发现弓形菌在肉制品、奶制品、海产品以及蔬菜中都有广泛分布。研究者们分别对弓形菌在禽肉[7-9]、牛肉[10-12]、猪肉[13-14]、羊肉[15-16]、乳制品[17-18]、海产品[13-14,19-20]等不同动物肉制品中的分布进行了研究。Hsu等根据10 年(2004—2014年)全球范围内弓形菌的调查数据对弓形菌在这些食品中的分布进行了总结并排序:乳制品(36.4%)>猪肉(36.3%)>海产品(32.3%)>牛肉(31.2%)>禽肉(26.4%)>羊肉(24.9%)>蔬菜(14%)[21]。但是,也有研究表明,弓形菌分离自猪肉、禽肉及相关制品的概率要大于其分离自牛羊肉及相关制品[21]。Rivas等在从澳大利亚超市和屠宰场采样得到的鸡肉糜馅、猪肉馅、牛肉馅和羊肉馅中分离到多株弓形菌,其中鸡肉样品中阳性率最高,高达73%,其次是猪肉、牛肉和羊肉[13]。根据Giacometti等对意大利奶牛场的研究,弓形菌在乳制品中较高的发现率可能与其在乳制品生产环境中较高的存在率有关[23]。与弯曲菌不同,弓形菌能够在有氧的条件下生长,其生理特性使弓形菌在食品加工、动物屠宰环境中大量存在[12,24-25]。有研究者通过分子生物学的方法对弓形菌进行分子分型和溯源研究,发现分离自零售食品与分离自食品加工设备上的弓形菌通常聚为一类,这说明加工过程中的环境污染是生鲜食品中弓形菌污染的主要原因之一[26]。另外,在低温保存(0~10 ℃)的食品中也能分离到弓形菌,Badilla-Ramírez等[8]从智利零售冷藏的鸡腿肉中分离到21 株弓形菌,表明弓形菌在较低冷藏温度下仍然能够存活。最近的研究表明,在蔬菜中也发现弓形菌的存在[25,27-28]。对普通家庭来说,蔬菜生食的几率较大,因此,通过生食蔬菜导致弓形菌致病可能成为一项潜在的食品安全风险。另一个潜在的传播途径则是通过海产品,越来越多的报道表明,弓形菌大量存在于新鲜贝类产品中[14,20,29],Collado等[14]在贝类中分离到11 种弓形菌,其中优势种为布氏弓形菌,占60.2%,Arcobacter molluscorum占21.2%,这两种弓形菌在贝类产品中发现率高达29.9%。另有研究报道,在蛤类产品中弓形菌的检出率为23.8%~100.0%,在贻贝中的检出率为33.3%~50.0%[14,29-30]。Collado等认为城市污水的排放是导致弓形菌在贝类产品中大量存在的主要原因[14]。

弓形菌广泛分布于环境中(表1),在地表水、水库、河流、污水处理厂、井水中都有分离到弓形菌的报道[31-32]。在俄亥俄州的一处海岛景区曾爆发过由于布氏弓形菌污染水源引起的游客和当地居民发生集体性肠炎的事件。Merga等采集英国9 个污水处理厂的未处理水样均检测出弓形菌,同时发现布氏弓形菌在城市污水中普遍存在[11]。近年来,越来越多的弓形菌感染案例被证明是由于饮用被弓形菌污染的水源或者食物而引起的,因此食品和饮用水也被视为弓形菌传播的主要途径[31,33]。另外,根据Houf[34]、Fera[35]、Petersen[36]等的报道,布氏弓形菌和嗜低温弓形菌可以寄生在宠物猫、宠物狗的身上,提示通过动物向人传播也可能是弓形菌潜在的传播渠道。

表1 弓形菌在食品中的分布

Table 1 Prevalence ofArcobacter in foods

来源分类 分离来源 分离菌株 国家 检出率/%(样品数)参考文献禽类鸡肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌、斯氏弓形菌 英国 62(94) [37]鸡肉 布氏弓形菌 西班牙 64.3(14) [14]鸡胸肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌 哥斯达黎加 56(50) [38]鸡肉 布氏弓形菌 澳大利亚 73(22) [13]鸭肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌 西班牙 40(5) [14]鸭肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌、斯氏弓形菌 伊朗 28(50) [39]鹅肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌 伊朗 10(50) [39]鹧鸪肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌、斯氏弓形菌 伊朗 11.3(80) [39]鸵鸟肉 布氏弓形菌 伊朗 3.3(60) [39]鹌鹑肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌、斯氏弓形菌 伊朗 12(100) [39]火鸡肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌 西班牙 33.3(30) [14]火鸡肉 布氏弓形菌 伊朗 12(100) [39]牛牛肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌、斯氏弓形菌 英国 34(108) [37]牛肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌 捷克 38.4(12) [40]牛肉 布氏弓形菌 澳大利亚 22(32) [13]进口牛肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌、斯氏弓形菌 马来西亚 46.8(22) [41]本地牛肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌 马来西亚 16.9(59) [41]猪肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌、斯氏弓形菌 英国 35(101) [37]猪肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌 西班牙 53(17) [14]猪肉 布氏弓形菌 澳大利亚 29(21) [13]羊 羊肉 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌、斯氏弓形菌 捷克 28.2(39) [40]羊肉 布氏弓形菌 澳大利亚 15(13) [13]兔 兔肉 布氏弓形菌 西班牙 10(10) [14]猪乳品生牛乳 布氏弓形菌 英国 46(101) [37]生牛乳 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌 马来西亚 5.8(86) [41]牛奶 弓形菌 土耳其 36(50) [18]奶酪 弓形菌 土耳其 56(56) [18]贻贝 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌、斯氏弓形菌、硝化弓形菌等11 种弓形菌 西班牙 41.1(56) [14]海产品 贻贝 弓形菌 西班牙 29.2(171) [20]蛤类 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌、斯氏弓形菌 西班牙 100(5) [19]牡蛎 弓形菌 西班牙 17.4(23) [20]蔬菜生菜 布氏弓形菌 意大利 20(65) [42]生菜 布氏弓形菌 西班牙 14(50) [27]菠菜 布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌 意大利 24.3(37) [42]芝麻菜 布氏弓形菌 意大利 27.3(33) [42]莴苣缬草 布氏弓形菌 意大利 52(25) [42]

2 流行病学特点

2.1 流行病学调查

人感染致病性弓形菌(布氏弓形菌和嗜低温弓形菌)通常会引起肠炎和菌血症[43-45]。斯氏弓形菌虽然从慢性肠炎病人的腹泻样品中分离出,但目前还没有直接的证据证明其具有致病性[46]。布氏弓形菌是最为常见的致病性弓形菌,在临床系统食源性病原菌优先级评级中,布氏弓形菌因引起全球性散发病例较多被划入“非常重要致病菌”[47]。根据部分病例报道,弓形菌感染引起的肠炎通常可以自愈,无需使用抗生素治疗[33,46]。而由于弓形菌与空肠弯曲菌形态以及引起疾病症状类似,弓形菌引起的疾病经常被误认为是空肠弯曲菌引起,造成弓形菌引起的疾病通常被严重低估。弓形菌感染致病的首次报道是1991年泰国发生的一起集体性儿童腹泻事件,从631 份临床样本中发现有15 例为弓形菌感染[48]。在另一份报道中,布氏弓形菌被证明造成10 名儿童反复性腹部痉挛[49]。很多研究表明,布氏弓形菌与腹泻、肠痉挛有关,还有可能引发菌血症和急性阑尾炎[45,50-51]。最近,比利时的一份研究表明,在过去8 年间,大约有3.5%曾认为是空肠弯曲菌引起的病例其实是由布氏弓形菌引起[52]。

关于弓形菌的流行病学调查资料较少,并不是因为弓形菌感染发病次数少,而是由于其较难分离,且与空肠弯曲菌非常相似,因此较难区分鉴定。现有的调查通常认为弓形菌的污染有以下两种途径:在养殖业中,由于高密度养殖及对粪污处理的疏忽,弓形菌通常会感染奶牛场的饮用水和新鲜牛奶,从而造成细菌在新鲜牛奶和饮用水中的循环增殖[53-54];而在禽畜屠宰厂中,禽肉制品高比例的弓形菌感染可能来自于加工过程中的加工设备和工业用水的污染[55]。

2.2 致病和毒力因子

关于弓形菌的致病机理和毒力因子的研究进展一直较为缓慢,2007年Miller等对于Arcobacter butzleri RM4018的全基因组测序促使该领域的研究踏上一个新的台阶[56]。他们通过对基因组进行注释,发现弓形菌存在多个与空肠弯曲菌毒力基因同源的基因;除此之外,他们还发现了部分与植物和动物病原体同源的假定毒力基因。目前根据与其他病原菌的同源比对,初步确定了9 个假定毒力基因:cadF、cj1349、ciaB、mviN、pldA、tlyA、hecA、hecB、irgA。其中cadF和cj1349编码外膜蛋白,增强与纤维连接蛋白的黏附力[57-58]。ciaB基因在弯曲菌中参与对宿主细胞的入侵[59]。mviN基因在大肠杆菌中是参与肽聚糖合成的关键基因[60]。pldA基因编码的外膜磷脂酶A与细胞溶血活性相关[55]。编码溶血素的基因tlyA在空肠弯曲菌中被证明参与上皮细胞Caco-2的黏附[62]。而在植物和动物病原菌中起非常重要作用的黏附素(丝状血凝素家族)由hecA基因编码。hecB基因编码相关溶血素蛋白[56]。irgA编码的铁离子调节外膜蛋白被证明与大肠杆菌的致病性相关[63]。

2.3 弓形菌的耐药性

大环内酯类和氟喹诺酮类抗生素是用于治疗弓形菌肠炎的常用药物,偶尔也会用到四环素类,同时氨基糖苷类抗生素也会用于治疗一些严重的细菌感染和多种细菌的交叉感染。Luangtongkum[64]、Rathlavath[65]等的研究表明,细菌的耐药性与长期暴露在这些抗生素环境中有关。很多分离自人体、禽肉、猪肉以及食品加工环境中的弓形菌都被证明对常见的人用和兽用抗生素具有一定的耐药性。据报道,弓形菌对甲氧苄氨嘧啶、联磺甲氧苄啶以及广谱β-内酰胺类如头孢菌素类特别是红霉素、环丙沙星和氨曲南都有较高的耐受性[39,66]。

Kiehlbauch等对78 株分离自动物和人源的布氏弓形菌进行耐药性筛查,发现高比例的布氏弓形菌对氨苄青霉素具有耐药性[67]。另外,分离自环境、动物和人源的弓形菌对氟喹诺酮类、大环内酯类、氯霉素类、氨基糖苷类、青霉素类、四环素类等抗生素具有较高比例的耐药性[68-71]。Son等对分离自鸡肉的布氏弓形菌和嗜低温弓形菌的耐药性进行研究,发现有71.8%的弓形菌都至少存在两重或多重耐药性[72]。另外,他们发现弓形菌中多重耐药菌的比例要比空肠弯曲菌高,其中布氏弓形菌中存在多重耐药性的比例最高,达72.9%[9]。造成这种高比例的原因可能有两个方面:一方面,在畜禽饲养过程中抗生素在动物治疗和预防过程中确实存在过度使用或滥用的问题;另一方面,目前缺乏对弓形菌抗生素耐药性评价的标准。由于缺乏专门针对弓形菌耐药性折点的判断标准,研究者采用的弓形菌耐药性分析方法各异,如采用美国临床和实验室标准协会建立的针对肠杆菌的耐药性检测方法;采用针对葡萄球菌的耐药性检测方法[70];或者采用美国国家抗生素耐药性检测体系提供的空肠弯曲菌耐药性标准[8]。总而言之,由于缺乏针对弓形菌耐药性的检测标准,造成了目前对于弓形菌耐药性的真实判断难度较大,且易造成有些抗生素耐药的漏判。

2.4 弓形菌耐药机制

目前的研究表明,弓形菌的耐药性主要来自于染色体上的基因突变[56,73],质粒上还未发现任何抗生素耐药基因[74]。如弓形菌对喹诺酮类抗生素的耐药性可能与其基因组中的DNA解旋酶A亚基(GyrA)的基因突变有关。DNA解旋酶由GyrA和GyrB两个亚基组成,它可以催化DNA形成负超螺旋结构,通常参与DNA的复制和RNA转录;该基因上有一个喹诺酮耐药特征区,其第254位从胞嘧啶到胸腺嘧啶的突变可以导致对新生霉素和喹诺酮类抗生素的耐药性[74]。这种突变在从病人样本中分离的对环丙沙星耐药的两株布氏弓形菌和一株嗜低温弓形菌中都有发现。Miller等通过对弓形菌多重耐药株RM4018进行全基因组测序分析,发现该菌缺少GyrA亚基特定位点的突变,推测其对喹诺酮的耐药机制可能在喹诺酮的吸收阶段,通过增加细胞通透性和提高外排泵的活性从而耐药[56]。对于氯霉素的耐药性,则是由于基因组中存在cat基因编码的氯霉素O-乙酰转移酶。同时,弓形菌RM4018对β-内酰胺类的耐药可能与基因组中存在3 个半乳糖苷酶同源基因有关[56]。对弓形菌的耐药性及耐药机制的研究目前尚处于起步阶段,仍存在很多空白。但是从已有的研究中可以看出,弓形菌耐药现状较为严重,这与抗生素的过度使用和滥用密不可分。为了控制弓形菌耐药菌株的不断增加,需要我们从农畜用药到人类公共医疗中对抗生素的使用更为慎重和严格。

3 弓形菌的实验室检测方法

对于弓形菌的实验室检测根据检测的原理通常分为两种方法:培养法和分子生物学方法。自1977年Ellis等[75]首次建立了该菌属的分离方法以来,已开发出了许多不同的分离方法。总体来说,通过培养进行弓形菌分离通常是一个较为繁琐的过程,需要一系列的富集培养基、选择培养基和非选择培养基,通常需要4~5 d。弓形菌第一次被分离是在一次采用半固体培养基分离钩端螺旋体的过程中[75]。此后,研究者采用各种不同的分离方法对弓形菌进行分离。在近几年的报道中,弓形菌的分离方法主要采用的是两步法:首先采用液体增菌培养基进行富集;再利用固体选择性培养基进行分离纯化[13]。用于增菌的液体培养基主要有:弓形菌特异性培养基(弓形菌培养基添加头孢哌酮、两性霉素B和替考拉宁)、弯曲菌增菌培养基、AEB培养基(弓形菌增菌培养基添加头孢哌酮、两性霉素B和替考拉宁)等。增菌后通过选择性平板或纤维素过滤的方法进行菌株分离,常用的选择性平板有:改性木炭头孢哌酮脱氧胆酸琼脂(modified charcoal cefoperazone desoxycholate agar,mCCDA)、弯曲菌选择性培养基(mCCDA添加头孢哌酮和两性霉素B)、Skirrow琼脂、Butzler培养基、CIN琼脂等。Merga等综合了近几年分离弓形菌的方法,对5 种方法进行比较,结果表明采用Arcobacter-specific broth培养基进行富集增菌,然后采用mCCDA固体培养基进行划线纯化具有较好的分离弓形菌的效果,可以分离到最多的弓形菌,且对其没有选择性[15]。

由于分离培养的方法所需试剂繁多、成本较高,对操作人员要求高,培养结果易受多种因素影响,检验周期通常需要5~7 d,不利于食源性突发疫情的快速诊断。采用分子生物学方法对弓形菌进行检测具有快速、准确、成本低等优势。目前应用较多的方法是聚合酶链式反应(polymerase chain reaction,PCR),很多研究者都相继采用PCR法对样品中的弓形菌进行检测[76-78]。其中,以Houf等使用的以16S rRNA和23S rRNA作为靶基因检测布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌和斯氏弓形菌的多重PCR法应用最为广泛[79]。Samarajeewa等[80]对高通量测序、变性梯度凝胶电泳、限制性片段长度多态性(restriction fragment length polymorphism,RFLP)和克隆建库测序4 种新型的检测方法进行了比较,发现所有这些方法都能够从已知的混合菌群中检出弓形菌。Levican等[81]于2013年对已发表的弓形菌PCR检测方法进行了比较和总结,发现近年来随着GenBank中16S rRNA和23S rRNA基因序列资源的不断丰富,Houf[79]报道的3 对引物的特异性大大降低,已无法保证检测结果的准确性,16S rRNA和23S rRNA也不再适合作为分辨布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌和斯氏弓形菌的的靶基因。

从目前的检测技术来看,单一检测技术往往在灵敏度或者准确性上有所局限,越来越多的研究者倾向于采用多种检测方法相结合来进行弓形菌的检测。Antolin等采用PCR结合酶联免疫吸附测定(enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay,ELISA)方法对禽肉中的弓形菌进行检测[82]。Vergis等采用16S rRNA基因PCR结合限制性内切酶(EcoRI、HindIII和SalI等)酶切,可以分辨包括弓形菌在内的8 种食源性病原菌(弓形菌、单核细胞增生李斯特氏菌、大肠埃希氏菌、沙门氏菌、志贺氏菌、弧菌、弯曲菌和耶尔森氏菌)[83]。Figueras等采用PCR结合RFLP方法(MseI酶切),能够分辨弓形菌属内的6 种弓形菌,其中包括嗜低温弓形菌的两个亚型[84]。弓形菌属细菌增加至17 种后,Figureras等采用同样的方法,发现可以分辨出该属内的10 种弓形菌,而另外7 种采用MseI酶切无法分辨的菌种可采用MnlI和BfaI酶切区分,该研究表明弓形菌属内的不同菌种在基因组水平上具有差异性[85]。Abdelbaqi等通过荧光定量PCR结合荧光共振能量转移的方法,在病人样本中检测到布氏弓形菌阳性[86]。通常情况下,从病例样本中采用传统的培养方法分离到布氏弓形菌和嗜低温弓形菌的概率为0.1%~3.0%[87]。分子生物学技术作为一种不依赖于培养的技术,摆脱了传统弓形菌检测鉴定过程中的培养条件、时间以及表型特征鉴定的限制,通常能够得到更为灵敏和准确的检测结果,同时也大大节约了检测时间(表2)。但是由于其仅针对细菌核酸进行检测,难以判断被检测细菌的生存状态,因此,能够快速准确判断细菌的数量及生存状态的检测方法还有待研究。

表2 弓形菌的分子生物学检测方法比较

Table 2 An overview of molecular diagnostic assays for the detection ofArcobacters

检测方法 靶基因 优点 不足 参考文献23S rRNA 一步区分布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌1A、1B亚型和斯氏弓形菌易将非弓形菌误判为弓形菌;嗜低温弓形菌亚型的区分不够严谨[80,88]16S rRNA和23S rRNA区分布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌和斯氏弓形菌;布氏弓形菌鉴定准确率可达100%嗜低温弓形菌和斯氏弓形菌易出现假阳性;不能区分其他弓形菌[79,81]多重PCRgyrA 可区分布氏弓形菌、嗜低温弓形菌、斯氏弓形菌和Arcobacter cibarius Arcobacter cibarius易误判为布氏弓形菌或斯氏弓形菌 [81,89]23S rRNA可区分包括布氏弓形菌在内的5 种弓形菌;100%鉴定布氏弓形菌、Arcobacter cibarius和Arcobacter thereuis无法鉴定Arcobacter trophiarum;易将其他弓形菌(Arcobacter def l uvii、Arcobacter ellisii、Arcobacter venerupis、Arcobacter suis)误判为布氏弓形菌[90]布氏弓形菌(rpoB/C);嗜低温弓形菌(23S rRNA)区分布氏弓形菌和嗜低温弓形菌 无法区分其他弓形菌 [78]定量PCR 23S rRNA 灵敏度较高;检测限提高至56 CFU/mL荧光仪器成本较高;对人员技术要求高 [91]多重荧光定量PCR弯曲菌属(16S rRNA);布氏弓形菌(hsp60)区分布氏弓形菌与其他弯曲菌属 对人员技术要求高 [77]PCR-ELISA 16S rRNA 区分弓形菌、弯曲菌和螺杆菌;可以定量操作较为复杂;定量误差较大 [82]16 rRNA+EcoRI/HindIII/SalI酶切区分弓形菌、单核细胞增生李斯特氏菌、大肠埃希氏菌、沙门氏菌、志贺氏菌、弧菌、弯曲菌和耶尔森氏菌对人员技术要求高 [83]PCR-RFLP 16 rRNA+MseI酶切 区分弓形菌属内6 种弓形菌 对人员技术要求高 [84]16 rRNA+MseI/MnlI/BfaI酶切MseI酶切可区分弓形菌属内10 种弓形菌;MnlI或BfaI酶切可区分6 种弓形菌 对人员技术要求高 [85]

4 结 语

弓形菌作为一种新型食源性致病菌,已逐渐引起国内外研究者的关注。本文对近几年来弓形菌在食品中的分布、流行病学特点和弓形菌的检测研究进展进行综述。与其他常见食源性致病菌的研究相比,对弓形菌的研究仍处于起步阶段。随着高通量测序、高分辨率质谱等手段在检测领域的发展,更快、更准确的弓形菌检测方法是今后研究的重要方向。另外,随着全球对食品安全的逐渐重视和食品安全溯源体系的逐步完善,对弓形菌在食品中的传播机制和溯源也是今后发展的重要方向。

参考文献:

[1] VANDAMME P, VANCANNEYT M, POT B. Polyphasic taxonomic study of the emended genus arcobacter withArcobacter butzleri comb. Nov. andArcobacter skirrowii sp. Nov., an aerotolerant bacterium isolated from veterinary specimens[J]. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, 1992, 42(3): 344-356.DOI:10.1099/00207713-42-3-344.

[2] MCCLUNG C R P D, DAVIS R E.Campylobacter nitrofigilis sp.Nov., a nitrogen-fixing bacterium associated with roots of spartina alternif l ora loisel[J]. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology,1983, 33(3): 605-612. DOI:10.1099/00207713-33-3-605.

[3] MANSFIELD L P, FORSYTHE S J. Arcobacter butzleri,A. skirrowii andA. cryaerophilus-potential emerging human pathogens[J].Reviews in Medical Microbiology, 2000, 11(3): 161-170.DOI:10.1097/00013542-200011030-00006.

[4] International Commission on Microbiological Specifications for Foods. Microorganisms in foods. in microbiological testing in food safety management[R]. New York: ICMSF, 2002.

[5] FLEMMING HANSEN D M, KATHARINA E P OLSEN. Arcobacter:an emerging food borne pathogen?[R]. Denmark: Danish Meat, 2007.

[6] RAMEES T P, DHAMA K, KARTHIK K, et al. Arcobacter: an emerging food-borne zoonotic pathogen, its public health concerns and advances in diagnosis and control: a comprehensive review[J].Veterinary Quarterly, 2017, 37(1): 136-161. DOI:10.1080/01652176.2017.1323355.

[7] HOUF K, DE VRIESE L A, DE ZUTTER L, et al. Development of a new protocol for the isolation and quantification of Arcobacter species from poultry products[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology,2001, 71(2): 189-196. DOI:10.1016/S0168-1605(01)00605-5.

[8] BADILLA-RAMÍREZ Y, FALLAS-PADILLA K L, FERNÁNDEZJARAMILLO H, et al. Survival capacity of Arcobacter butzleri inoculated in poultry meat at two different refrigeration temperatures[J]. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo, 2016, 58(1): 1-3. DOI:10.1590/S1678-9946201658022.

[9] SON I, ENGLEN M D, BERRANG M E, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Arcobacter and Campylobacter from broiler carcasses[J].International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 2007, 29(4): 451-455.DOI:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.10.016.

[10] GOLLA S C, MURANO E A, JOHNSON L G, et al. Determination of the occurrence of Arcobacter butzleri in beef and dairy cattle from Texas by various isolation methods[J]. Journal of Food Protection,2002, 65(12): 1849-1853. DOI:10.4315/0362-028X-65.12.1849.

[11] MERGA J Y, WILLIAMS N J, MILLER W G, et al. Exploring the diversity of Arcobacter butzleri from cattle in the UK using MLST and whole genome sequencing[J]. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(2): 1-12.DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0055240.

[12] SHAH A H, SALEHA A A, ZUNITA Z, et al. Prevalence, distribution and antibiotic resistance of emergent Arcobacter spp. from clinically healthy cattle and goats[J]. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases,2013, 60(1): 9-16. DOI:10.1111/j.1865-1682.2012.01311.x.

[13] RIVAS L, FEGAN N, VANDERLINDE P. Isolation and characterisation of Arcobacter butzleri from meat[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2004, 91(1): 31-41. DOI:10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00328-3.

[14] COLLADO L, GUARRO J, FIGUERAS M J. Prevalence of Arcobacter in meat and shellfish[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2009,72(5): 1102-1106. DOI:10.4315/0362-028X-72.5.1102.

[15] MERGA J Y, LEATHERBARROW A J H, WINSTANLEY C, et al.Comparison of Arcobacter isolation methods, and diversity of Arcobacter spp. in Cheshire, United Kingdom[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 77(5): 1646-1650. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01964-10.

[16] SHIRZAD A H, TABATABAEI M, KHOSHBAKHT R, et al.Occurrence and antimicrobial resistance of emergent Arcobacter spp.isolated from cattle and sheep in Iran[J]. Comparative Immunology,Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 2016, 44: 37-40. DOI:10.1016/j.cimid.2015.12.002.

[17] SCULLION R, HARRINGTON C S, MADDEN R H. Prevalence of Arcobacter spp. in raw milk and retail raw meats in Northern Ireland[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2006, 69(8): 1986-1990.DOI:10.1016/j.cimid.2015.12.002.

[18] YESILMEN S, VURAL A, ERKAN M E, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Arcobacter species in cow milk,water buffalo milk and fresh village cheese[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2014, 188: 11-14. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.07.006.

[19] COLLADO L, CLEENWERCK I, VAN TRAPPEN S, et al. Arcobacter mytili sp. Nov., an indoxyl acetate-hydrolysis-negative bacterium isolated from mussels[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2009, 59(6): 1391-1396. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.003749-0.

[20] LEVICAN A, COLLADO L, YUSTES C, et al. Higher water temperature and incubation under aerobic and microaerobic conditions increase the recovery and diversity of Arcobacter spp. from shellfish[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014. 80(1):385-391. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.003749-0.

[21] HSU T T D, LEE J. Global distribution and prevalence of Arcobacter in food and water[J]. Zoonoses Public Health, 2015, 62(8): 579-589.DOI:10.1111/zph.12215.

[22] PHILLIPS C A. Arcobacter spp. in food; isolation, identification and control[J]. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2001, 12(8): 263-275. DOI:10.1016/S0924-2244(01)00090-5.

[23] GIACOMETTI F, LUCCHI A, MANFREDA G, et al. Occurrence and genetic diversity of Arcobacter butzleri in an artisanal dairy plant in Italy[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2013, 79(21):6665-6669. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02404-13.

[24] RASMUSSEN L, KJELDGAARD J, CHRISTENSEN J, et al.Multilocus sequence typing and biocide tolerance of Arcobacter butzleri from danish broiler carcasses[J]. BMC Research Notes, 2013,6(1): 322-328. DOI:10.1186/1756-0500-6-322.

[25] HAUSDORF L, NEUMANN M, BERGMANN I, et al. Occurrence and genetic diversity of Arcobacter spp. in a spinach-processing plant and evaluation of two Arcobacter-specific quantitative PCR assays[J]. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 2013, 36(4): 235-243. DOI:10.1016/j.syapm.2013.02.003.

[26] ADESIJI Y, OLOKE J, EMIKPE B, et al. Arcobacter, an emerging opportunistic food borne pathogen: a review[J]. African Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, 2014, 43: 1-7. DOI:10.1016/j.syapm. 2013.02.003.

[27] GONZALEZ A, FERRUS M A. Study of Arcobacter spp.contamination in fresh lettuces detected by different cultural and molecular methods[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology,2011, 145(1): 311-314. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.11.018.

[28] HAUSDORF L, MUNDT K, WINZER M, et al. Characterization of the cultivable microbial community in a spinach-processing plant using MALDI-TOF MS[J]. Food Microbiology, 2013, 34(2): 406-411.DOI:10.1016/j.fm.2012.10.008.

[29] NIEVA-ECHEVARRIA B, MARTINEZ-MALAXETXEBARRIA I,GIRBAU C, et al. Prevalence and genetic diversity of Arcobacter in food products in the north of Spain[J]. Journal of Food Protection,2013, 76(8): 1447-1450. DOI:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-014.

[30] COLLADO L, JARA R, VÁSQUEZ N, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes of Arcobacter isolates recovered from edible bivalve molluscs[J]. Food Control, 2014, 46: 508-512. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.06.013.

[31] FONG T T, MANSFIELD L S, WILSON D L, et al. Massive microbiological groundwater contamination associated with a waterborne outbreak in lake Erie, South Bass Island, Ohio[J].Environmental Health Perspectives, 2007, 115(6): 856-864.DOI:10.1289/ehp.9430.

[32] PEREZ-CATALUNA A, SALAS-MASSO N, FIGUERAS M J.Arcobacter canalis sp. Nov., isolated from a water canal contaminated with urban sewage[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2018, 68(4): 1258-1264. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.002662.

[33] LAPPI V, ARCHER J R, CEBELINSKI E, et al. An outbreak of foodborne illness among attendees of a wedding reception in wisconsin likely caused by Arcobacter butzleri[J]. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease, 2013, 10(3): 250-255. DOI:10.1089/fpd.2012.1307.

[34] HOUF K, DE SMET S, BARÉ J, et al. Dogs as carriers of the emerging pathogen Arcobacter[J]. Veterinary Microbiology, 2008,130(1/2): 208-213. DOI:10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.01.006.

[35] FERA M T, LA CAMERA E, CARBONE M, et al. Pet cats as carriers of Arcobacter spp. in Southern Italy[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2009, 106(5): 1661-1666. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.04133.x.

[36] PETERSEN R F, HARRINGTON C S, KORTEGAARD H E, et al.A PCR-DGGE method for detection and identification of Campylobacter, Helicobacter, Arcobacter and related Epsilobacteria and its application to saliva samples from humans and domestic pets[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2007, 103(6): 2601-2615.DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03515.x.

[37] SCULLION R, HARRINGTON C S, MADDEN A H. Prevalence of Arcobacter spp. in raw milk and retail raw meats in Northern Ireland[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2006, 69(8): 1986-1990.DOI:10.4315/0362-028X-69.8.1986.

[38] FALLAS-PADILLA K L, RODRÍGUEZ-RODRÍGUEZ C E,JARAMILLO H F, et al. Arcobacter: comparison of isolation methods,diversity, and potential pathogenic factors in commercially retailed chicken breast meat from Costa Rica[J]. Journal of Food Protection,2014, 77(6): 880-884. DOI:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-368.

[39] RAHIMI E. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Arcobacter species isolated from poultry meat in Iran[J]. British Poultry Science,2014, 55(2): 174-180. DOI:10.1080/00071668.2013.878783.

[40] PEJCHALOVÁ M, DOSTÁLÍKOVÁ E, SLÁMOVÁ M, et al.Prevalence and diversity of Arcobacter spp. in the Czech Republic[J].Journal of Food Protection, 2008, 71(4): 719-727. DOI:10.4315/0362-028X-71.4.719.

[41] SHAH A H, SALEHA A A, MURUGAIYAH M, et al. Prevalence and distribution of Arcobacter spp. in raw milk and retail raw beef[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2012, 75(8): 1474-1478.DOI:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-487.

[42] MOTTOLA A, BONERBA E, BOZZO G, et al. Occurrence of emerging food-borne pathogenic Arcobacter spp. isolated from pre-cut (ready-to-eat) vegetables[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2016, 236: 33-37. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.07.012.

[43] FIGUERAS M J, LEVICAN A, PUJOL I, et al. A severe case of persistent diarrhoea associated with Arcobacter cryaerophilus but attributed to Campylobacter sp. and a review of the clinical incidence of Arcobacter spp.[J]. New Microbes and New Infections, 2014, 2(2):31-37. DOI:10.1002/2052-2975.35.

[44] WOO P C, CHONG K T, LEUNG K, et al. Identification of Arcobacter cryaerophilus isolated from a traffic accident victim with bacteremia by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing[J]. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease, 2001, 40(3): 125-127. DOI:10.1016/S0732-8893(01)00261-9.

[45] YAN J J, KO W C, HUANG A H, et al. Arcobacter butzleri bacteremia in a patient with liver cirrhosis[J]. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 2000, 99(2): 166-169.

[46] WYBO I, BREYNAERT J, LAUWERS S, et al. Isolation of Arcobacter skirrowii from a patient with chronic diarrhea[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2004, 42(4): 1851-1852. DOI:10.1128/JCM.42.4.1851-1852.2004.

[47] CAEDOEN S, VAN HUFFEL X, BERKVENS D, et al. Evidencebased semiquantitative methodology for prioritization of foodborne zoonoses[J]. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease, 2009, 6(9): 1083-1096. DOI:10.1089/fpd.2009.0291.

[48] TAYLOR D N, KIEHLBAUCH J A, TEE W, et al. Isolation of group 2 aerotolerant Campylobacter species from Thai children with diarrhea[J]. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 1991, 163(5): 1062-1067. DOI:10.1093/infdis/163.5.1062.

[49] VANDAMME P, PUGINA P, BENZI G, et al. Outbreak of recurrent abdominal cramps associated with Arcobacter butzleri in an Italian school[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 1992, 30(9): 2335-2337.

[50] LERNER J, BRUMBERGER V, PREAC-MURSIC V. Severe diarrhea associated with Arcobacter butzleri[J]. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, 1994, 13: 660-662. DOI:10.1007/BF01973994.

[51] ON S L W, STACEY A, SMYTH J. Isolation of Arcobacter butzleri from a neonate with bacteraemia[J]. The Journal of Infection, 1995,31(3): 225-227. DOI:10.1016/S0163-4453(95)80031-X.

[52] VANDENBERG O, DEDISTE A, HOUF K, et al. Arcobacter species in humans[J]. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2004, 10(10): 1863-1867.DOI:10.3201/eid1010.040241.

[53] FERRERIRA S, OLEASTRO M, DOMINGUES F C. Occurrence,genetic diversity and antibiotic resistance of Arcobacter sp. in a dairy plant[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2017, 123(4): 1019-1026.DOI:10.1111/jam.13538.

[54] SERRAINO A, GIACOMETTI F. Short communication: occurrence of arcobacter species in industrial dairy plants[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2014, 97(4): 2061-2065. DOI:10.3168/jds.2013-7682.

[55] JRIBI H, SELLAMI H, HASSENA A B, et al. Prevalence of putative virulence genes in Campylobacter and Arcobacter species isolated from poultry and poultry by-products in Tunisia[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2017, 80(10): 1705-1710. DOI:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-16-509.

[56] MILLER W G, PARKER C T, RUBENFIELD M, et al. The complete genome sequence and analysis of the epsilonproteobacterium Arcobacter butzleri[J]. PLoS ONE, 2007, 2(12): 1-7. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0001358.

[57] MONTEVILLE M R, YOON J E, KONKEL M E, Maximal adherence and invasion of INT 407 cells by Campylobacter jejuni requires the CadF outer-membrane protein and microfilament reorganization[J].Microbiology, 2003. 149(1): 153-165. DOI:10.1099/mic.0.25820-0.

[58] FLANAGAN R C, NEAL-MCKINNEY J M, DHILLON A S, et al.Examination of Campylobacter jejuni putative adhesins leads to the identification of a new protein, designated FlpA, required for chicken colonization[J]. Infection and Immunity, 2009, 77(6): 2399-2407.DOI:10.1128/IAI.01266-08.

[59] KONKEL M E, KIM B J, RIVERA-AMILL V, et al. Bacterial secreted proteins are required for the internaliztion of Campylobacter jejuni into cultured mammalian cells[J]. Molecular Microbiology, 1999,32(4): 691-701. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01376.x.

[60] INOUE A, MURATA Y, TAKAHASHI H, et al. Involvement of an essential gene, mvin, in murein synthesis in Escherichia coli[J].Journal of Bacteriology, 2008, 190(21): 7298-7301. DOI:10.1128/JB.00551-08.

[61] GRANT K A, BELANDIA I U, DEKKER N, et al. Molecular characterization of plda, the structural gene for a phospholipase a from Campylobacter coli, and its contribution to cell-associated hemolysis[J]. Infection and Immunity, 1997, 65(4): 1172-1180.DOI:10.1016/S0928-8244(97)00015-1.

[62] SALAMASZYŃSKA-GUZ A, KLIMUSZKO D. Functional analysis of the Campylobacter jejuni cj0183 and cj0588 genes[J]. Current Microbiology, 2008, 56(6): 592-596. DOI:10.1007/s00284-008-9130-z.

[63] JOHNSON J R, JELACIC S, SCHOENING L M, et al. The IrgA homologue adhesin iha is an Escherichia coli virulence factor in murine urinary tract infection[J]. Infection and Immunity, 2005, 73(2):965-971. DOI:10.1128/IAI.73.2.965-971.2005.

[64] LUANGTONGKUM T, JEON B, HAN J, et al. Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter: emergence, transmission and persistence[J]. Future Microbiology, 2009, 4(2): 189-200. DOI:10.2217/17460913.4.2.189.

[65] RATHLAVATH S, KOHLI V, SINGH A S, et al. Virulence genotypes and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of arcobacter butzleri isolated from seafood and its environment[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2017, 263: 32-37. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.10.005.

[66] VAN DEN ABEELE A M, VOGELAERS D, VANLAERE E, et al.Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Arcobacter butzleri and Arcobacter cryaerophilus strains isolated from Belgian patients[J].Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2016, 71(5): 1241-1244.DOI:10.1093/jac/dkv483.

[67] KIEHLBAUCH J A, BRENNER D J, NICHOLSON M A, et al.Campylobacter-butzleri sp. Nov. isolated from humans and animals with diarrheal illness[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 1991, 29:376-385.

[68] FERREIRA S, FRAQUEZA M J, QUEIROZ J A, et al. Genetic diversity, antibiotic resistance and biofilm-forming ability of Arcobacter butzleri isolated from poultry and environment from a portuguese slaughterhouse[J]. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy,2013, 162(1): 82-88. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.01.003.

[69] ABAY S, KAYMAN T, HIZLISOY H, et al. In vitro antibacterial susceptibility of Arcobacter butzleri isolated from different sources[J].Journal of Veterinary Medical Science, 2012, 74(5): 613-616.DOI:10.1292/jvms.11-0487.

[70] VANDENBERG O. Antimicrobial susceptibility of clinical isolates of non-jejuni/coli Campylobacters and Arcobacters from Belgium[J].Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2006, 57(5): 908-913.DOI:10.1093/jac/dkl080.

[71] KAYMAN T, ABAY S, HIZLISOY H, et al. Emerging pathogen Arcobacter spp. in acute gastroenteritis: molecular identification,antibiotic susceptibilities and genotyping of the isolated Arcobacters[J]. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 2012, 61(10): 1439-1444. DOI:10.1099/jmm.0.044594-0.

[72] SON I, ENGLEN M D, BERRANG M E, et al. Prevalence of Arcobacter and Campylobacter on broiler carcasses during processing[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2007,113(1): 16-22. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.06.033.

[73] ABDELBAQI K, MÉNARD A, PROUZET-MAULEON V, et al.Nucleotide sequence of the gyrA gene of Arcobacter species and characterization of human ciprof l oxacin-resistant clinical isolates[J].FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology, 2007, 49(3): 337-345.DOI:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00208.x.

[74] DOUIDAH L, DE ZUTTER L, VAN NIEUWERBURGH F, et al.Presence and analysis of plasmids in human and animal associated Arcobacter species[J]. PLoS ONE, 2014, 9: 1-10. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0085487.

[75] ELLIS W A, NEILL S D, O’BRIEN J J, et al. Isolation of spirillum/vibrio-like organisms from pig foetuses[J]. Veterinary Record, 1977,102: 451-452. DOI:10.1136/vr.102.5.106-a.

[76] SUAREZ D L, WESLEY I V, LARSON D J. Detection of Arcobacter species in gastric samples from swine[J]. Veterinary Microbiology,1997, 57(4): 325-336. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00107-7.

[77] DE BOER R F, OTT A, GUREN P, et al. Detection of Campylobacter species and Arcobacter butzleri in stool samples by use of real-time multiplex PCR[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2013, 51(1): 253-259. DOI:10.1128/JCM.01716-12.

[78] BRIGHTWELL G, MOWAT E, CLEMENS R, et al. Development of a multiplex and real time PCR assay for the specific detection of Arcobacter butzleri and Arcobacter cryaerophilus[J]. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 2007, 68(2): 318-325. DOI:10.1016/j.mimet.2006.09.008.

[79] HOUF K. Development of a multiplex pcr assay for the simultaneous detection and identification of Arcobacter butzleri, Arcobacter cryaerophilus and Arcobacter skirrowii[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters,2000, 193(1): 89-94. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09407.x.

[80] SAMARAJEEWA A D, HAMMAD A, MASSON L, et al. Comparative assessment of next-generation sequencing, denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis, clonal restriction fragment length polymorphism and cloning-sequencing as methods for characterizing commercial microbial consortia[J]. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 2015,108: 103-111. DOI:10.1016/j.mimet.2014.11.013.

[81] LEVICAN A, FIGUERAS M. Performance of five molecular methods for monitoring Arcobacter spp.[J]. BMC Microbiology, 2013, 13: 220-226. DOI:10.1186/1471-2180-13-220.

[82] ANTOLIN A, GONZALEZ I, GARCIA T, et al. Arcobacter spp.enumeration in poultry meat using a combined PCR-ELISA assay[J]. Meat Science, 2001, 59(2): 169-174. DOI:10.1016/S0309-1740(01)00067-5.

[83] VERGIS J, NEGI M, POHARKAR K, et al. 16S rRNA PCR followed by restriction endonuclease digestion: a rapid approach for genus level identification of important enteric bacterial pathogens[J]. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 2013, 95(3): 353-356. DOI:10.1016/j.mimet.2013.10.001.

[84] FIGUERAS M J, COLLADO L, GUARRO J. A new 16S rDNA-RFLP method for the discrimination of the accepted species of Arcobacter[J].Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease, 2008, 62(1): 11-15.DOI:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.09.019.

[85] FIGUERAS M J, LEVICAN A, COLLADO L. Updated 16S rRNARFLP method for the identification of all currently characterised Arcobacter spp.[J]. BMC Microbiology, 2012, 12: 292-298.DOI:10.1186/1471-2180-12-292.

[86] ABDELBAQI K, BUISSONNIERE A, PROUZET-MAULEON V, et al.Development of a real-time fluorescence resonance energy transfer PCR to detect Arcobacter species[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology,2007, 45(9): 3015-3021. DOI:10.1128/JCM.00256-07.

[87] COLLADO L, FIGUERAS M J. Taxonomy, epidemiology, and clinical relevance of the genus Arcobacter[J]. Clinical Microbiology Reviews,2011, 24(1): 174-192. DOI:10.1128/CMR.00034-10.

[88] KABEYA H, KOBAYASHI Y, MARUYAMA S, et al. One-step polymerase chain reaction-based typing of Arcobacter species[J].International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2003, 81(2): 163-168.DOI:10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00197-6.

[89] PENTIMALLI D, PEGELS N, GARCÍA T, et al. Specific PCR detection of Arcobacter butzleri, Arcobacter cryaerophilus, Arcobacter skirrowii,and Arcobacter cibarius in chicken meat[J]. Journal of Food Protection,2009, 72(7): 1491-1495. DOI:10.4315/0362-028X-72.7.1491.

[90] DOUIDAH L, DE ZUTTER L, VANDAMME P, et al. Identification of five human and mammal associated Arcobacter species by a novel multiplex-PCR assay[J]. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 2010,80(3): 281-286. DOI:10.1016/j.mimet.2010.01.009.

[91] GONZÁLEZ A, SUSKI J, FERRÚS M A. Rapid and accurate detection of Arcobacter contamination in commercial chicken products and wastewater samples by real-time polymerase chain reaction[J].Foodborne Pathogens and Disease, 2010, 7(3): 327-338. DOI:10.1089/fpd.2009.0368.

Prevalence and Detection of Arcobacter as an Emerging Foodborne Pathogen in Foods: A Review

WU Yufan1, WANG Xiang2, CUI Siyu1, SHAO Jingdong1,*

(1. Technology Center of Zhangjiagang Entry-Exit Inspection and Quarantine Bureau, Zhangjiagang 215600, China; 2. School of Medical Instrument and Food Engineering, University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai 200093, China)

Abstract: Arcobacter is an emerging foodborne zoonotic pathogen. It was first known as ‘aerotolerant campylobacters’ due to its morphological resemblance and close relatedness to the genus Campylobacter. In the Arcobacter genus, A. butzleri,A. cryaerophilus and A. skirrowii are predominantly associated with human diseases (gastroenteritis, severe diarrhea and bacteremia). Arcobacter has been reported to be widely distributed in livestock and poultry products, and the environment.Its high prevalence in livestock and poultry products may be ascribed to post-slaughter contamination due to either the contaminated production facilities or processed water. Arcobacter is difficult to differentiate from Campylobacter due to their high physiological similarity. Molecular biological methods have been popular for laboratorial diagnosis of Arcobacters at the genus and species level. As an emerging foodborne zoonotic pathogen, Arcobacter has been a major concern for researchers.However, unlike other common foodborne pathogens, the current knowledge about Arcobacter is still limited. This review summarizes the current knowledge concerning Arcobacter distribution and its epidemiological characteristics as well as recent advances in its laboratorial diagnosis. Our aim is to provide valuable information for researchers interested in this area.

Keywords: Arcobacter; foodborne pathogen; prevalence; epidemiological characteristics; laboratorial diagnosis

收稿日期:2018-03-14

基金项目:“十三五”国家重点研发计划重点专项(2016YFD0401102);江苏出入境检验检疫局青年基金项目(2016KJ49;2017KJ53)

第一作者简介:吴瑜凡(1987—)(ORCID: 0000-0002-2029-374X),女,工程师,博士,研究方向为食源性致病菌检测和分子分型。E-mail: wuyufan126@126.com

*通信作者简介:邵景东(1969—)(ORCID: 0000-0002-8236-2624),男,高级工程师,硕士,研究方向为食品微生物检验。E-mail: shaojd@jsciq.gov.cn

DOI:10.7506/spkx1002-6630-20180314-181

中图分类号:TS207.4

文献标志码:A

文章编号:1002-6630(2019)07-0281-08

引文格式:吴瑜凡, 王翔, 崔思宇, 等. 潜在食源性致病菌弓形菌在食品中的分布及检测研究进展[J]. 食品科学, 2019, 40(7):281-288. DOI:10.7506/spkx1002-6630-20180314-181. http://www.spkx.net.cn

WU Yufan, WANG Xiang, CUI Siyu, et al. Prevalence and detection of Arcobacter as an emerging foodborne pathogen in foods: a review[J]. Food Science, 2019, 40(7): 281-288. (in Chinese with English abstract) DOI:10.7506/spkx1002-6630-20180314-181. http://www.spkx.net.cn